Oil as the Substrate of Power: Before Politics, Energy

This essay inaugurates a series of three texts on oil as the material base of modern power. Starting from the history of energy, the text investigates how oil shaped geopolitics, the State, and markets, paving the way for an analysis of energy crises and their unfolding in the present.

1/3

Oil as the Substrate of Power: Before Politics, Energy

History is a dynamic concept: borders change, power shifts hands, and over time some assets become more valuable than others. Nevertheless, even with the becoming of time, every political order rests on a material base. Before crystallizing into laws, discourses, or ideologies, power manifests itself materially, as the capacity to organize and direct. It is there that energy takes on a central role. Power is tied to the ways in which energy is extracted, distributed, and converted into authority.

Oil emerges as one of the main examples of how energy and power are intimately connected. It is the energy that allowed modernity to break physical limits, accelerate historical time, and transform the planet into an interconnected system governed by flows.

From the industrial revolution to the energy revolution

In the nineteenth century, the hegemony of coal sustained the British Industrial Revolution. Factories, railways, and cities grew around mines. Power was heavy, localized, and predictable. But this model carried a technical limit: it depended on geographic proximity and fixed infrastructure.

The turning point began in 1859, with the drilling of the first commercial oil well in Titusville, Pennsylvania. What seemed like a marginal event inaugurated a new ontology of energy: portable, concentrated, transportable by sea. From that moment on, the geopolitical map was never the same.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, this transformation ceased to be merely economic and became military. In 1911, Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the British Admiralty, decided to convert the naval fleet from coal to oil. This cannot be seen as a merely technical choice; it was a strategic decision that redefined the British Empire’s capacity to project power.

The First World War (1914–1918) confirmed this shift. Tanks, trucks, and airplanes became decisive in the clashes of a war fought in trenches, causing oil to cease being merely a resource and to become the point of imbalance—or balance—of the conflict.

Oil, State, and territory

In the interwar period, the relationship between oil and sovereignty intensified. In 1928, the Red Line Agreement redrew control over Middle Eastern reserves among Western powers. There is here an unprecedented point in history: power distancing itself from the old empires toward contemporary geopolitics. This is not a new version of classical colonialism, but something more sophisticated: energy control and political power.

After the Second World War, this logic consolidated itself. The Bretton Woods Agreement (1944) organized the international monetary system, while oil guaranteed the material infrastructure of that system. Strong currency, strong industry, strong military, all fed by the same energy source.

In 1945, the meeting between Franklin D. Roosevelt and King Abdulaziz of Saudi Arabia sealed the oil–security alliance that would shape American foreign policy for decades. Oil became integrated into the architecture of the dollar, creating the embryo of what would later become the petrodollar.

Here, energy and economy cease to be separate domains. Oil sustains growth, stabilizes currencies, and allows permanent military deficits. The modern State reaches its mature form: technically efficient, fiscally expansive, and geopolitically interventionist.

Crisis as the language of the system

The illusion of stability collapses in the 1970s. In 1973, the OPEC embargo reveals something fundamental: energy is not neutral. The oil shock is not merely a price increase, but an ontological crisis of the industrial system.

Inflation, recession, and monetary instability become symptoms of a deeper problem: the structural dependence on a politically unstable energy source.

The second shock, in 1979, with the Iranian Revolution, confirms that oil functions as a geoeconomic weapon. From that moment on, crises cease to be exceptions and become recurring mechanisms of global power reorganization.

The financial market absorbs this logic. Futures, derivatives, and risk pricing become abstract forms of anticipating conflicts. War comes to be partially fought before the battlefield, in charts and curves of expectation.

Energy, technique, and abstraction

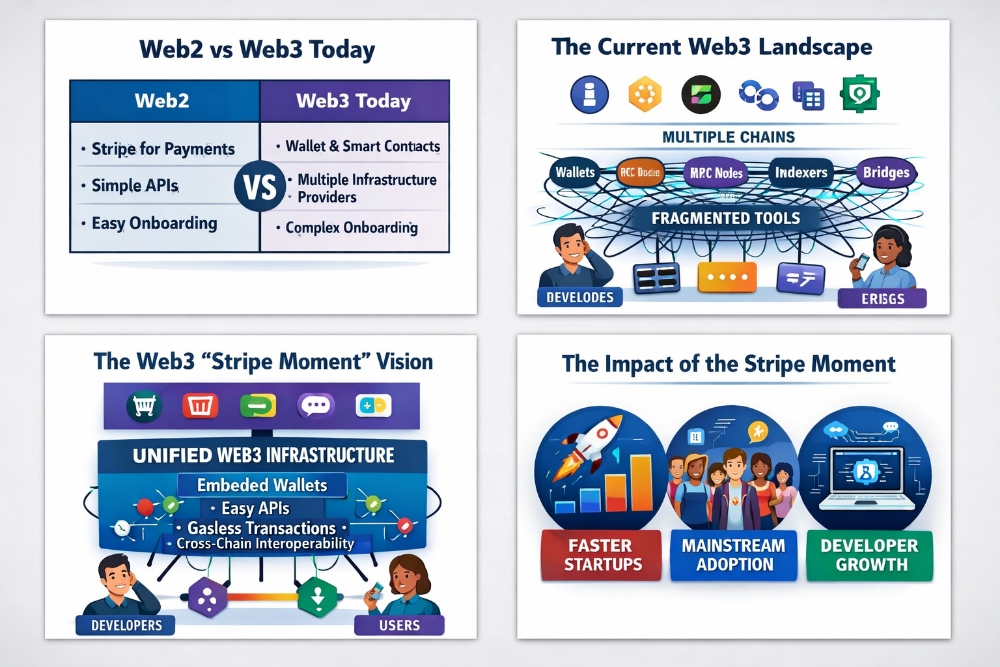

The end of the twentieth century marks a silent inflection. Oil remains central, but its ability to organize the world on its own begins to fail. Productive chains become digitalized, capital becomes faster than physical logistics, and information acquires strategic value of its own.

However, technique never eliminates the material base: it merely conceals it. Servers, networks, data centers, and financial systems remain dependent on energy, now distributed across increasingly abstract layers.

It is in this context that the crypto market emerges as a technical expression of an ancient philosophical intuition: trust is not natural, it is constructed; value is not given, it is produced by systems of consensus.

Bitcoin, by tying value to verifiable energy cost, reintroduces into the digital plane a truth forgotten by the traditional financial system: in an inflationary global economy, the real value of money exceeds its purely symbolic value.

The present as continuity of the past

Oil, therefore, is not a residue of the twentieth century: it is its structural legacy. It continues to organize wars, justify sanctions, and shape markets, even when discourse points toward transitions and ruptures.

Every profound energy transition generates an unstable historical interval. A period in which old power is still capable of causing destruction, but no longer able to guarantee order.

It is within this interval that we live.

And it is within this interval that markets, from the barrel to the block, reveal their true function: not to predict the future, but to absorb the shock between incompatible historical times. It is at this point that crisis ceases to be an exception and begins to operate as the recurring language of the system.