Fortress’ conservation policies threaten the food security of rural populations

Barriers created by “fortress conservation” — as in the near-total sectioning off of land for conservation without human interference — are threatening important dietary diversity for the up to 1.5 billion people around the world who rely on wild foods, from bushmeat to wild vegetables and fruit.

Conservation, especially when modelled on notions of “pristine nature” — environments untouched by human influence — can create obstacles by limiting access to important food sources. We must shift from strict fortress conservation to more integrated, sustainable use of rural landscapes if we are to achieve both biodiversity conservation and dietary outcomes.

Policymakers must take this into account and design policies that better inform global, regional and national commitments to food security and nutrition — especially in the context an ever-changing and unpredictable climate.

These policies must recognize people’s rights of access to these landscapes to ensure dietary diversity in rural settings. Policies for sustainable forestry are also a key component of sustainable food systems.

Settling down

Human societies were nomadic for the majority of our history. In turn, traditional diets were mostly comprised of wild foods, both plants and animals, that were harvested from the surrounding environment.

However, over time, communities became increasingly sedentary and relied more and more on foods that were cultivated, rather than those collected from the wild.

This process dramatically accelerated in the last century with the Green Revolution beginning in the 1940s, characterized by the increased dominance of monoculture agriculture. This shift is the greatest driver of forest and other habitat loss globally, resulting in the substantial simplification of our diets.

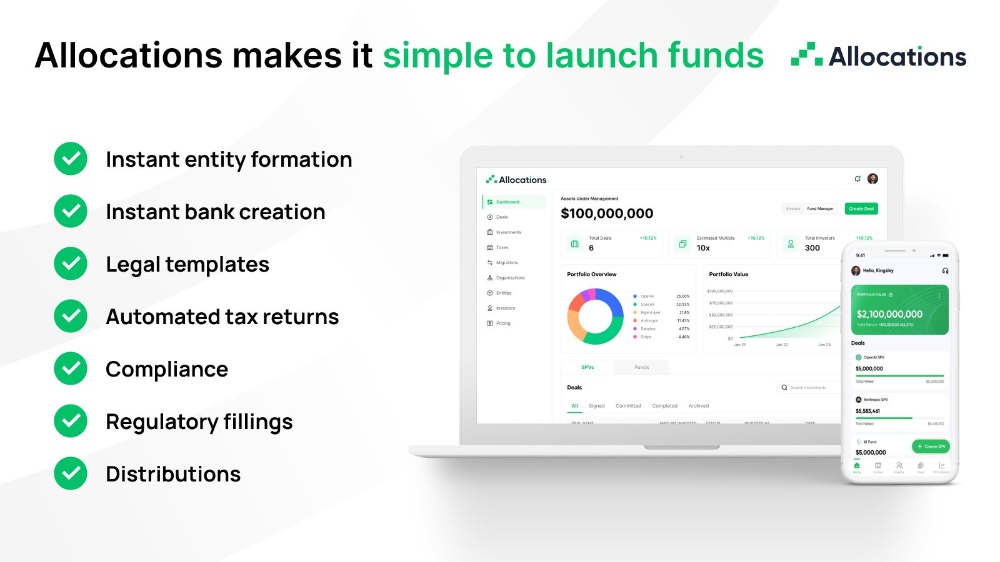

A tractor sprays pesticides on a soybean field.

A tractor sprays pesticides on a soybean field. Monoculture farming can produce high yields, but at the cost of extreme fragility to external climatic and environmental shocks. (Shutterstock)

However, we have since learned that biodiverse wild and naturalized species are integral in rural food consumption, contributing to diverse diets, better nutrition and overall health and well-being, often for the poorest members of society. In other words, diversity in diets is linked with better nutrition and improved overall health.

Up to 1.5 billion people globally depend on wild foods for nutrition and dietary diversity, particularly in the tropics. Building policies that protect people’s rights to access these landscapes is of paramount importance to ensure such dietary diversity in many rural settings.

We must devote attention to people living in rural areas around the planet, where their access to wild foods — including those found in forests — has become limited. That’s cutting off important sources of healthy food and nutrition.

Read more: How culturally appropriate diets can be a pathway to food security in the Canadian Arctic

Global initiatives to set aside land for biodiversity conservation Barriers created by “fortress conservation” — as in the near-total sectioning off of land for conservation without human interference — are threatening important dietary diversity for the up to 1.5 billion people around the world who rely on wild foods, from bushmeat to wild vegetables and fruit.

Conservation, especially when modelled on notions of “pristine nature” — environments untouched by human influence — can create obstacles by limiting access to important food sources. We must shift from strict fortress conservation to more integrated, sustainable use of rural landscapes if we are to achieve both biodiversity conservation and dietary outcomes.

Policymakers must take this into account and design policies that better inform global, regional and national commitments to food security and nutrition — especially in the context an ever-changing and unpredictable climate.

These policies must recognize people’s rights of access to these landscapes to ensure dietary diversity in rural settings. Policies for sustainable forestry are also a key component of sustainable food systems.

Settling down

Human societies were nomadic for the majority of our history. In turn, traditional diets were mostly comprised of wild foods, both plants and animals, that were harvested from the surrounding environment.

However, over time, communities became increasingly sedentary and relied more and more on foods that were cultivated, rather than those collected from the wild.

This process dramatically accelerated in the last century with the Green Revolution beginning in the 1940s, characterized by the increased dominance of monoculture agriculture. This shift is the greatest driver of forest and other habitat loss globally, resulting in the substantial simplification of our diets.

A tractor sprays pesticides on a soybean field.

A tractor sprays pesticides on a soybean field. Monoculture farming can produce high yields, but at the cost of extreme fragility to external climatic and environmental shocks. (Shutterstock)

However, we have since learned that biodiverse wild and naturalized species are integral in rural food consumption, contributing to diverse diets, better nutrition and overall health and well-being, often for the poorest members of society. In other words, diversity in diets is linked with better nutrition and improved overall health.

Up to 1.5 billion people globally depend on wild foods for nutrition and dietary diversity, particularly in the tropics. Building policies that protect people’s rights to access these landscapes is of paramount importance to ensure such dietary diversity in many rural settings.

We must devote attention to people living in rural areas around the planet, where their access to wild foods — including those found in forests — has become limited. That’s cutting off important sources of healthy food and nutrition.

Read more: How culturally appropriate diets can be a pathway to food security in the Canadian Arctic

Global initiatives to set aside land for bBarriers created by “fortress conservation” — as in the near-total sectioning off of land for conservation without human interference — are threatening important dietary diversity for the up to 1.5 billion people around the world who rely on wild foods, from bushmeat to wild vegetables and fruit.

Conservation, especially when modelled on notions of “pristine nature” — environments untouched by human influence — can create obstacles by limiting access to important food sources. We must shift from strict fortress conservation to more integrated, sustainable use of rural landscapes if we are to achieve both biodiversity conservation and dietary outcomes.

Policymakers must take this into account and design policies that better inform global, regional and national commitments to food security and nutrition — especially in the context an ever-changing and unpredictable climate.

These policies must recognize people’s rights of access to these landscapes to ensure dietary diversity in rural settings. Policies for sustainable forestry are also a key component of sustainable food systems.

Settling down

Human societies were nomadic for the majority of our history. In turn, traditional diets were mostly comprised of wild foods, both plants and animals, that were harvested from the surrounding environment.

However, over time, communities became increasingly sedentary and relied more and more on foods that were cultivated, rather than those collected from the wild.

This process dramatically accelerated in the last century with the Green Revolution beginning in the 1940s, characterized by the increased dominance of monoculture agriculture. This shift is the greatest driver of forest and other habitat loss globally, resulting in the substantial simplification of our diets.

A tractor sprays pesticides on a soybean field.

A tractor sprays pesticides on a soybean field. Monoculture farming can produce high yields, but at the cost of extreme fragility to external climatic and environmental shocks. (Shutterstock)

However, we have since learned that biodiverse wild and naturalized species are integral in rural food consumption, contributing to diverse diets, better nutrition and overall health and well-being, often for the poorest members of society. In other words, diversity in diets is linked with better nutrition and improved overall health.

Up to 1.5 billion people globally depend on wild foods for nutrition and dietary diversity, particularly in the tropics. Building policies that protect people’s rights to access these landscapes is of paramount importance to ensure such dietary diversity in many rural settings.

We must devote attention to people living in rural areas around the planet, where their access to wild foods — including those found in forests — has become limited. That’s cutting off important sources of healthy food and nutrition.

Read more: How culturally appropriate diets can be a pathway to food security in the Canadian Arctic

Global initiatives to set aside land for bBarriers created by “fortress conservation” — as in the near-total sectioning off of land for conservation without human interference — are threatening important dietary diversity for the up to 1.5 billion people around the world who rely on wild foods, from bushmeat to wild vegetables and fruit.

Conservation, especially when modelled on notions of “pristine nature” — environments untouched by human influence — can create obstacles by limiting access to important food sources. We must shift from strict fortress conservation to more integrated, sustainable use of rural landscapes if we are to achieve both biodiversity conservation and dietary outcomes.

Policymakers must take this into account and design policies that better inform global, regional and national commitments to food security and nutrition — especially in the context an ever-changing and unpredictable climate.

These policies must recognize people’s rights of access to these landscapes to ensure dietary diversity in rural settings. Policies for sustainable forestry are also a key component of sustainable food systems.

Settling down

Human societies were nomadic for the majority of our history. In turn, traditional diets were mostly comprised of wild foods, both plants and animals, that were harvested from the surrounding environment.

However, over time, communities became increasingly sedentary and relied more and more on foods that were cultivated, rather than those collected from the wild.

This process dramatically accelerated in the last century with the Green Revolution beginning in the 1940s, characterized by the increased dominance of monoculture agriculture. This shift is the greatest driver of forest and other habitat loss globally, resulting in the substantial simplification of our diets.

A tractor sprays pesticides on a soybean field.

A tractor sprays pesticides on a soybean field. Monoculture farming can produce high yields, but at the cost of extreme fragility to external climatic and environmental shocks. (Shutterstock)

However, we have since learned that biodiverse wild and naturalized species are integral in rural food consumption, contributing to diverse diets, better nutrition and overall health and well-being, often for the poorest members of society. In other words, diversity in diets is linked with better nutrition and improved overall health.

Up to 1.5 billion people globally depend on wild foods for nutrition and dietary diversity, particularly in the tropics. Building policies that protect people’s rights to access these landscapes is of paramount importance to ensure such dietary diversity in many rural settings.

We must devote attention to people living in rural areas around the planet, where their access to wild foods — including those found in forests — has become limited. That’s cutting off important sources of healthy food and nutrition.

Read more: How culturally appropriate diets can be a pathway to food security in the Canadian Arctic

Global initiatives to set aside land for bBarriers created by “fortress conservation” — as in the near-total sectioning off of land for conservation without human interference — are threatening important dietary diversity for the up to 1.5 billion people around the world who rely on wild foods, from bushmeat to wild vegetables and fruit.

Conservation, especially when modelled on notions of “pristine nature” — environments untouched by human influence — can create obstacles by limiting access to important food sources. We must shift from strict fortress conservation to more integrated, sustainable use of rural landscapes if we are to achieve both biodiversity conservation and dietary outcomes.

Policymakers must take this into account and design policies that better inform global, regional and national commitments to food security and nutrition — especially in the context an ever-changing and unpredictable climate.

These policies must recognize people’s rights of access to these landscapes to ensure dietary diversity in rural settings. Policies for sustainable forestry are also a key component of sustainable food systems.

Settling down

Human societies were nomadic for the majority of our history. In turn, traditional diets were mostly comprised of wild foods, both plants and animals, that were harvested from the surrounding environment.

However, over time, communities became increasingly sedentary and relied more and more on foods that were cultivated, rather than those collected from the wild.

This process dramatically accelerated in the last century with the Green Revolution beginning in the 1940s, characterized by the increased dominance of monoculture agriculture. This shift is the greatest driver of forest and other habitat loss globally, resulting in the substantial simplification of our diets.

A tractor sprays pesticides on a soybean field.

A tractor sprays pesticides on a soybean field. Monoculture farming can produce high yields, but at the cost of extreme fragility to external climatic and environmental shocks. (Shutterstock)

However, we have since learned that biodiverse wild and naturalized species are integral in rural food consumption, contributing to diverse diets, better nutrition and overall health and well-being, often for the poorest members of society. In other words, diversity in diets is linked with better nutrition and improved overall health.

Up to 1.5 billion people globally depend on wild foods for nutrition and dietary diversity, particularly in the tropics. Building policies that protect people’s rights to access these landscapes is of paramount importance to ensure such dietary diversity in many rural settings.

We must devote attention to people living in rural areas around the planet, where their access to wild foods — including those found in forests — has become limited. That’s cutting off important sources of healthy food and nutrition.

Read more: How culturally appropriate diets can be a pathway to food security in the Canadian Arctic

Global initiatives to set aside land for bBarriers created by “fortress conservation” — as in the near-total sectioning off of land for conservation without human interference — are threatening important dietary diversity for the up to 1.5 billion people around the world who rely on wild foods, from bushmeat to wild vegetables and fruit.

Conservation, especially when modelled on notions of “pristine nature” — environments untouched by human influence — can create obstacles by limiting access to important food sources. We must shift from strict fortress conservation to more integrated, sustainable use of rural landscapes if we are to achieve both biodiversity conservation and dietary outcomes.

Policymakers must take this into account and design policies that better inform global, regional and national commitments to food security and nutrition — especially in the context an ever-changing and unpredictable climate.

These policies must recognize people’s rights of access to these landscapes to ensure dietary diversity in rural settings. Policies for sustainable forestry are also a key component of sustainable food systems.

Settling down

Human societies were nomadic for the majority of our history. In turn, traditional diets were mostly comprised of wild foods, both plants and animals, that were harvested from the surrounding environment.

However, over time, communities became increasingly sedentary and relied more and more on foods that were cultivated, rather than those collected from the wild.

This process dramatically accelerated in the last century with the Green Revolution beginning in the 1940s, characterized by the increased dominance of monoculture agriculture. This shift is the greatest driver of forest and other habitat loss globally, resulting in the substantial simplification of our diets.

A tractor sprays pesticides on a soybean field.

A tractor sprays pesticides on a soybean field. Monoculture farming can produce high yields, but at the cost of extreme fragility to external climatic and environmental shocks. (Shutterstock)

However, we have since learned that biodiverse wild and naturalized species are integral in rural food consumption, contributing to diverse diets, better nutrition and overall health and well-being, often for the poorest members of society. In other words, diversity in diets is linked with better nutrition and improved overall health.

Up to 1.5 billion people globally depend on wild foods for nutrition and dietary diversity, particularly in the tropics. Building policies that protect people’s rights to access these landscapes is of paramount importance to ensure such dietary diversity in many rural settings.

We must devote attention to people living in rural areas around the planet, where their access to wild foods — including those found in forests — has become limited. That’s cutting off important sources of healthy food and nutrition.

Read more: How culturally appropriate diets can be a pathway to food security in the Canadian Arctic

Global initiatives to set aside land for bBarriers created by “fortress conservation” — as in the near-total sectioning off of land for conservation without human interference — are threatening important dietary diversity for the up to 1.5 billion people around the world who rely on wild foods, from bushmeat to wild vegetables and fruit.

Conservation, especially when modelled on notions of “pristine nature” — environments untouched by human influence — can create obstacles by limiting access to important food sources. We must shift from strict fortress conservation to more integrated, sustainable use of rural landscapes if we are to achieve both biodiversity conservation and dietary outcomes.

Policymakers must take this into account and design policies that better inform global, regional and national commitments to food security and nutrition — especially in the context an ever-changing and unpredictable climate.

These policies must recognize people’s rights of access to these landscapes to ensure dietary diversity in rural settings. Policies for sustainable forestry are also a key component of sustainable food systems.

Settling down

Human societies were nomadic for the majority of our history. In turn, traditional diets were mostly comprised of wild foods, both plants and animals, that were harvested from the surrounding environment.

However, over time, communities became increasingly sedentary and relied more and more on foods that were cultivated, rather than those collected from the wild.

This process dramatically accelerated in the last century with the Green Revolution beginning in the 1940s, characterized by the increased dominance of monoculture agriculture. This shift is the greatest driver of forest and other habitat loss globally, resulting in the substantial simplification of our diets.

A tractor sprays pesticides on a soybean field.

A tractor sprays pesticides on a soybean field. Monoculture farming can produce high yields, but at the cost of extreme fragility to external climatic and environmental shocks. (Shutterstock)

However, we have since learned that biodiverse wild and naturalized species are integral in rural food consumption, contributing to diverse diets, better nutrition and overall health and well-being, often for the poorest members of society. In other words, diversity in diets is linked with better nutrition and improved overall health.

Up to 1.5 billion people globally depend on wild foods for nutrition and dietary diversity, particularly in the tropics. Building policies that protect people’s rights to access these landscapes is of paramount importance to ensure such dietary diversity in many rural settings.

We must devote attention to people living in rural areas around the planet, where their access to wild foods — including those found in forests — has become limited. That’s cutting off important sources of healthy food and nutrition.

Read more: How culturally appropriate diets can be a pathway to food security in the Canadian Arctic

Global initiatives to set aside land for bBarriers created by “fortress conservation” — as in the near-total sectioning off of land for conservation without human interference — are threatening important dietary diversity for the up to 1.5 billion people around the world who rely on wild foods, from bushmeat to wild vegetables and fruit.

Conservation, especially when modelled on notions of “pristine nature” — environments untouched by human influence — can create obstacles by limiting access to important food sources. We must shift from strict fortress conservation to more integrated, sustainable use of rural landscapes if we are to achieve both biodiversity conservation and dietary outcomes.

Policymakers must take this into account and design policies that better inform global, regional and national commitments to food security and nutrition — especially in the context an ever-changing and unpredictable climate.

These policies must recognize people’s rights of access to these landscapes to ensure dietary diversity in rural settings. Policies for sustainable forestry are also a key component of sustainable food systems.

Settling down

Human societies were nomadic for the majority of our history. In turn, traditional diets were mostly comprised of wild foods, both plants and animals, that were harvested from the surrounding environment.

However, over time, communities became increasingly sedentary and relied more and more on foods that were cultivated, rather than those collected from the wild.

This process dramatically accelerated in the last century with the Green Revolution beginning in the 1940s, characterized by the increased dominance of monoculture agriculture. This shift is the greatest driver of forest and other habitat loss globally, resulting in the substantial simplification of our diets.

A tractor sprays pesticides on a soybean field.

A tractor sprays pesticides on a soybean field. Monoculture farming can produce high yields, but at the cost of extreme fragility to external climatic and environmental shocks. (Shutterstock)

However, we have since learned that biodiverse wild and naturalized species are integral in rural food consumption, contributing to diverse diets, better nutrition and overall health and well-being, often for the poorest members of society. In other words, diversity in diets is linked with better nutrition and improved overall health.

Up to 1.5 billion people globally depend on wild foods for nutrition and dietary diversity, particularly in the tropics. Building policies that protect people’s rights to access these landscapes is of paramount importance to ensure such dietary diversity in many rural settings.

We must devote attention to people living in rural areas around the planet, where their access to wild foods — including those found in forests — has become limited. That’s cutting off important sources of healthy food and nutrition.

Read more: How culturally appropriate diets can be a pathway to food security in the Canadian Arctic

Global initiatives to set aside land for bBarriers created by “fortress conservation” — as in the near-total sectioning off of land for conservation without human interference — are threatening important dietary diversity for the up to 1.5 billion people around the world who rely on wild foods, from bushmeat to wild vegetables and fruit.

Conservation, especially when modelled on notions of “pristine nature” — environments untouched by human influence — can create obstacles by limiting access to important food sources. We must shift from strict fortress conservation to more integrated, sustainable use of rural landscapes if we are to achieve both biodiversity conservation and dietary outcomes.

Policymakers must take this into account and design policies that better inform global, regional and national commitments to food security and nutrition — especially in the context an ever-changing and unpredictable climate.

These policies must recognize people’s rights of access to these landscapes to ensure dietary diversity in rural settings. Policies for sustainable forestry are also a key component of sustainable food systems.

Settling down

Human societies were nomadic for the majority of our history. In turn, traditional diets were mostly comprised of wild foods, both plants and animals, that were harvested from the surrounding environment.

However, over time, communities became increasingly sedentary and relied more and more on foods that were cultivated, rather than those collected from the wild.

This process dramatically accelerated in the last century with the Green Revolution beginning in the 1940s, characterized by the increased dominance of monoculture agriculture. This shift is the greatest driver of forest and other habitat loss globally, resulting in the substantial simplification of our diets.

A tractor sprays pesticides on a soybean field.

A tractor sprays pesticides on a soybean field. Monoculture farming can produce high yields, but at the cost of extreme fragility to external climatic and environmental shocks. (Shutterstock)

However, we have since learned that biodiverse wild and naturalized species are integral in rural food consumption, contributing to diverse diets, better nutrition and overall health and well-being, often for the poorest members of society. In other words, diversity in diets is linked with better nutrition and improved overall health.

Up to 1.5 billion people globally depend on wild foods for nutrition and dietary diversity, particularly in the tropics. Building policies that protect people’s rights to access these landscapes is of paramount importance to ensure such dietary diversity in many rural settings.

We must devote attention to people living in rural areas around the planet, where their access to wild foods — including those found in forests — has become limited. That’s cutting off important sources of healthy food and nutrition.

Read more: How culturally appropriate diets can be a pathway to food security in the Canadian Arctic

Global initiatives to set aside land for bBarriers created by “fortress conservation” — as in the near-total sectioning off of land for conservation without human interference — are threatening important dietary diversity for the up to 1.5 billion people around the world who rely on wild foods, from bushmeat to wild vegetables and fruit.

Conservation, especially when modelled on notions of “pristine nature” — environments untouched by human influence — can create obstacles by limiting access to important food sources. We must shift from strict fortress conservation to more integrated, sustainable use of rural landscapes if we are to achieve both biodiversity conservation and dietary outcomes.

Policymakers must take this into account and design policies that better inform global, regional and national commitments to food security and nutrition — especially in the context an ever-changing and unpredictable climate.

These policies must recognize people’s rights of access to these landscapes to ensure dietary diversity in rural settings. Policies for sustainable forestry are also a key component of sustainable food systems.

Settling down

Human societies were nomadic for the majority of our history. In turn, traditional diets were mostly comprised of wild foods, both plants and animals, that were harvested from the surrounding environment.

However, over time, communities became increasingly sedentary and relied more and more on foods that were cultivated, rather than those collected from the wild.

This process dramatically accelerated in the last century with the Green Revolution beginning in the 1940s, characterized by the increased dominance of monoculture agriculture. This shift is the greatest driver of forest and other habitat loss globally, resulting in the substantial simplification of our diets.

A tractor sprays pesticides on a soybean field.

A tractor sprays pesticides on a soybean field. Monoculture farming can produce high yields, but at the cost of extreme fragility to external climatic and environmental shocks. (Shutterstock)

However, we have since learned that biodiverse wild and naturalized species are integral in rural food consumption, contributing to diverse diets, better nutrition and overall health and well-being, often for the poorest members of society. In other words, diversity in diets is linked with better nutrition and improved overall health.

Up to 1.5 billion people globally depend on wild foods for nutrition and dietary diversity, particularly in the tropics. Building policies that protect people’s rights to access these landscapes is of paramount importance to ensure such dietary diversity in many rural settings.

We must devote attention to people living in rural areas around the planet, where their access to wild foods — including those found in forests — has become limited. That’s cutting off important sources of healthy food and nutrition.

Read more: How culturally appropriate diets can be a pathway to food security in the Canadian Arctic

Global initiatives to set aside land for biodiversity conservation iodiversity conservation iodiversity conservation iodiversity conservation iodiversity conservation iodiversity conservation iodiversity conservation iodiversity conservation iodiversity conservation