Amazigh Writing Across Centuries

Across the mountains, deserts, and coasts of North Africa (Tamazgha), the Amazigh people have carried a deep legacy of resilience. Their languages and identities endured centuries of shifting empires and cultural currents, leaving behind traces not only in oral traditions but also in enduring scripts.

The story of Amazigh writing is a journey from ancient carvings in stone to modern revival, each stage reflecting both continuity and adaptation.

1. Libyco-Berber Inscriptions (1st Millennium BCE – Early CE): Messages from Antiquity

Long before foreign empires reached North Africa, Amazigh communities inscribed their presence into stone. These early writings, known as Libyco-Berber inscriptions, appeared between the 1st millennium BCE and the early centuries of our era.

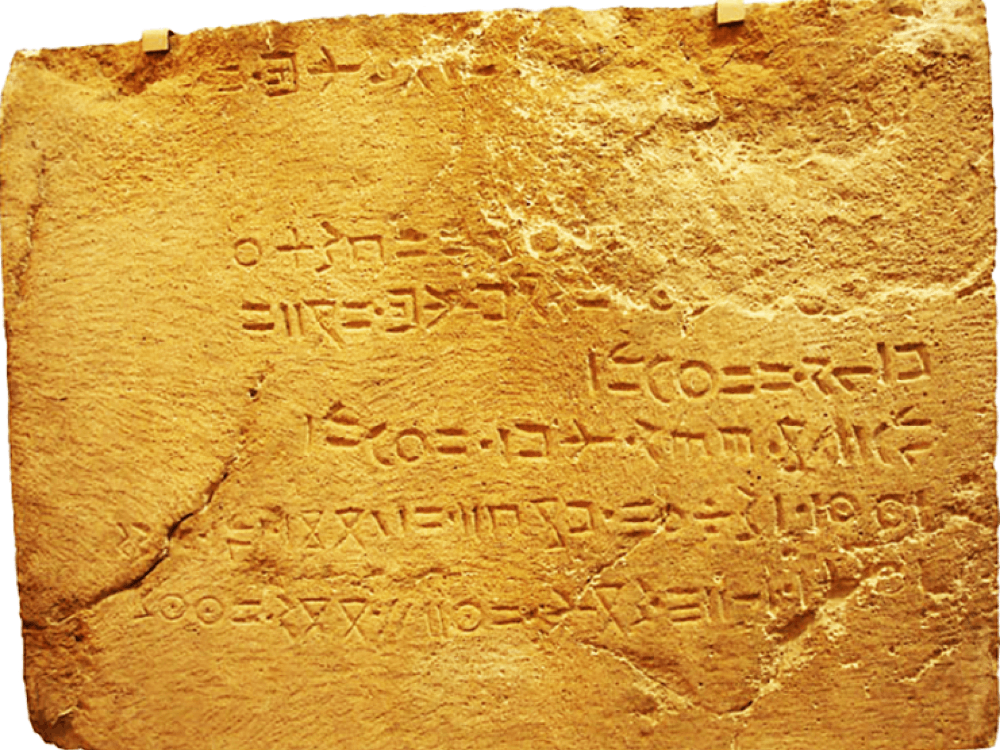

Inscription from the Mausoleum of Atban (Libyan text).

British Museum. Photo Sophie A. de Beaune © DR

They are sparse, concise, and enigmatic—yet they reveal a people determined to anchor memory and identity into the physical landscape. Found on tombs, stelae, and rocky surfaces, these inscriptions carried personal names, clan markers, and signs of belonging. They represent one of the oldest testimonies to the Amazigh connection with literacy.

2. Kingdoms of Numidia and Mauretania (2nd Century BCE – 1st Century CE): Writing in Dialogue

As Amazigh kingdoms like Numidia and Mauretania flourished, writing gained a new dimension. It became a tool not only for remembrance but also for diplomacy and power.

Inscriptions from this era often appear in two languages: Libyco-Berber alongside Punic or Latin. This bilingualism mirrored the dual worlds Amazigh rulers inhabited—rooted in local traditions yet engaged with the Mediterranean powers of their time.

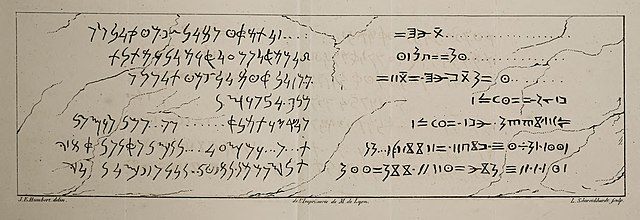

The first published sketch of the Punic-Libyan Bilingual

inscription of Dougga -146 BC. (Jean Emile Humbert)

These royal inscriptions revealed hierarchies, alliances, and religious dedications, and they stand today as proof of how Amazigh rulers projected their authority through written word.

3. Tifinagh of the Sahara (1st Millennium BCE → Present): A Living Script in the Desert

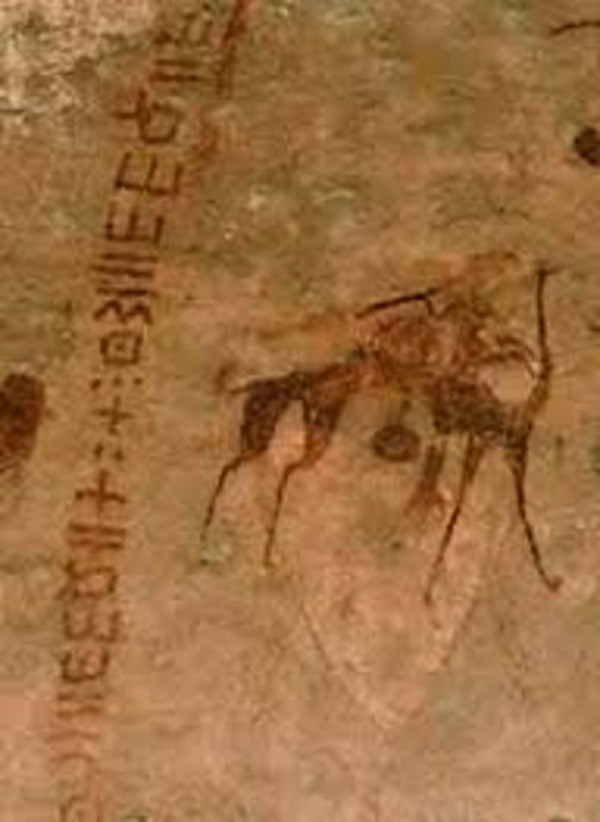

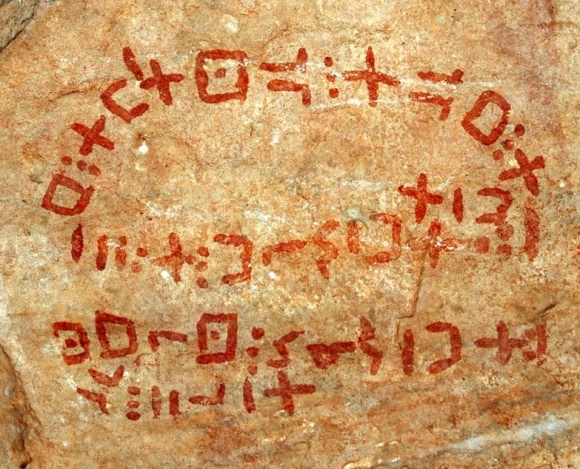

While many ancient scripts vanished with their civilizations, the Amazigh script endured in the Sahara. Tifinagh, descended from Libyco-Berber forms, became the signature of Tuareg communities spread across Algeria, Mali, Niger, and Libya.

For centuries, it was inscribed not just on stone, but on everyday objects—tools, jewelry, and even textiles—embedding writing into the rhythm of daily life. Tifinagh was not used for long chronicles or administrative archives, but rather as a marker of identity, love, and spirituality.

Its survival into the present day is a rare phenomenon, showing the intimate way Amazigh culture wove writing into both the monumental and the personal.

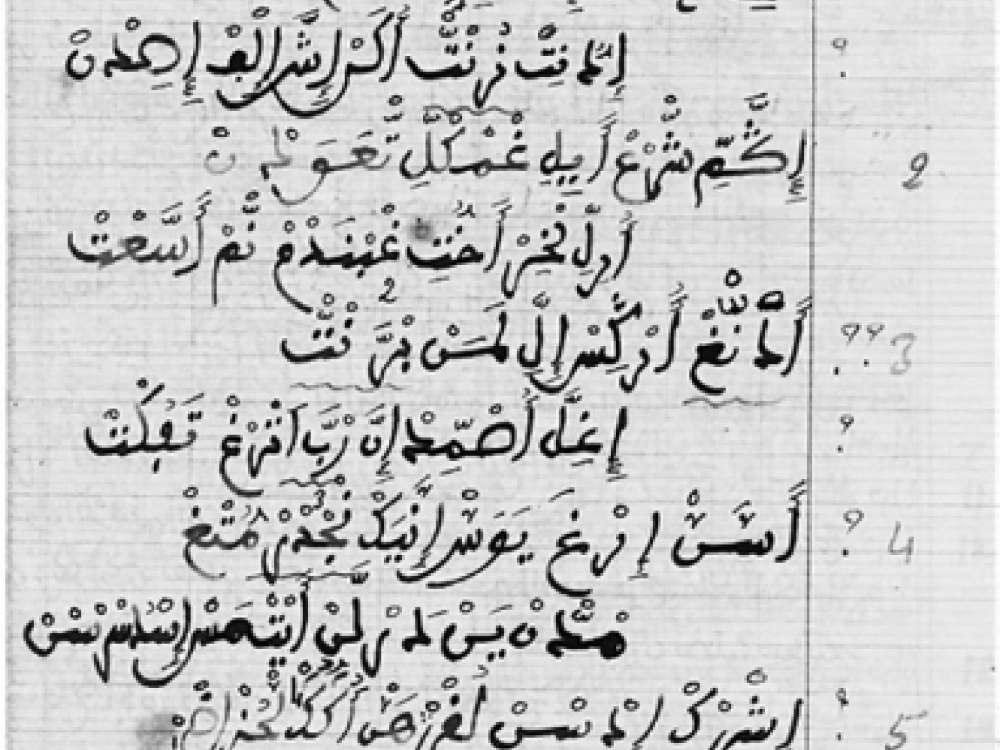

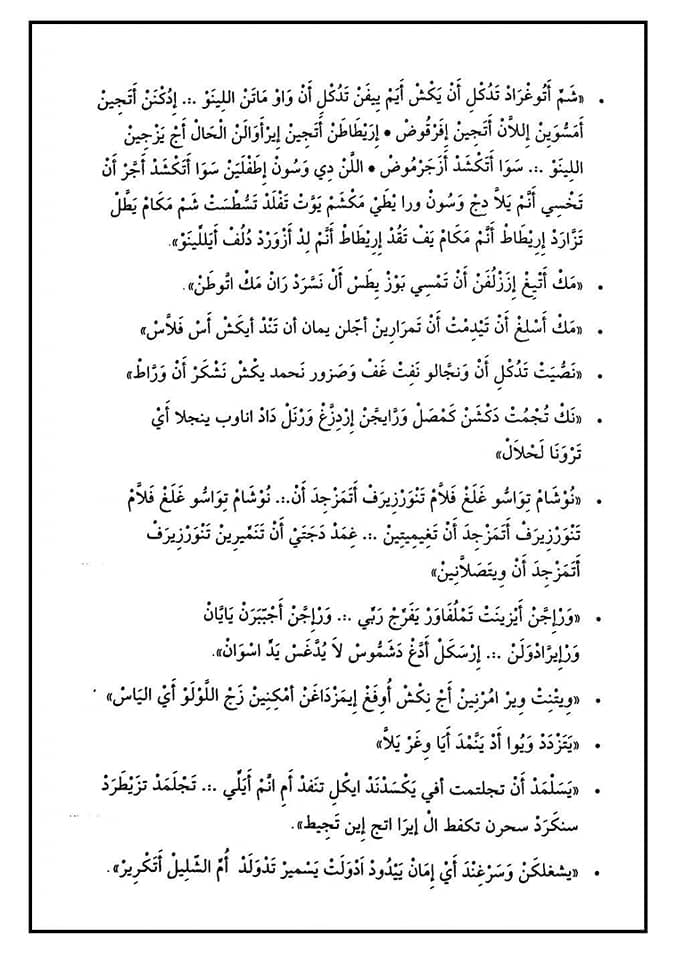

4. Medieval Amazigh Texts (From 10th Century CE): Voices in Arabic Script

With the expansion of Islam and the spread of Arabic literacy, Amazigh communities began to adopt Arabic letters to preserve their own languages. From the 10th century onward, manuscripts appear containing poetry, legal opinions, and translations of religious texts.

The oldest texts in the Nafusa Berber language (1009-1105 CE)

Excerpts from Chleuh manuscripts (1500-1599 CE)

These works, while written in Arabic script, were unmistakably Amazigh in spirit and content. This stage reveals the adaptability of Amazigh identity: embracing the prestige of Arabic writing while ensuring that local languages continued to find expression in written form.

5. Amazigh Writing in the French Colonial Period (1830-1962 CE)

During the French colonial period in North Africa, Amazigh writing survived in different forms despite pressures of Arabization and colonial assimilation. In Morocco, Algeria, and the Sahara, many Amazigh communities continued to write in Arabic script, producing poetry, religious commentaries, and legal texts.

These manuscripts preserved cultural identity and circulated within local schools, mosques, and villages, keeping the Amazigh language alive under foreign rule.

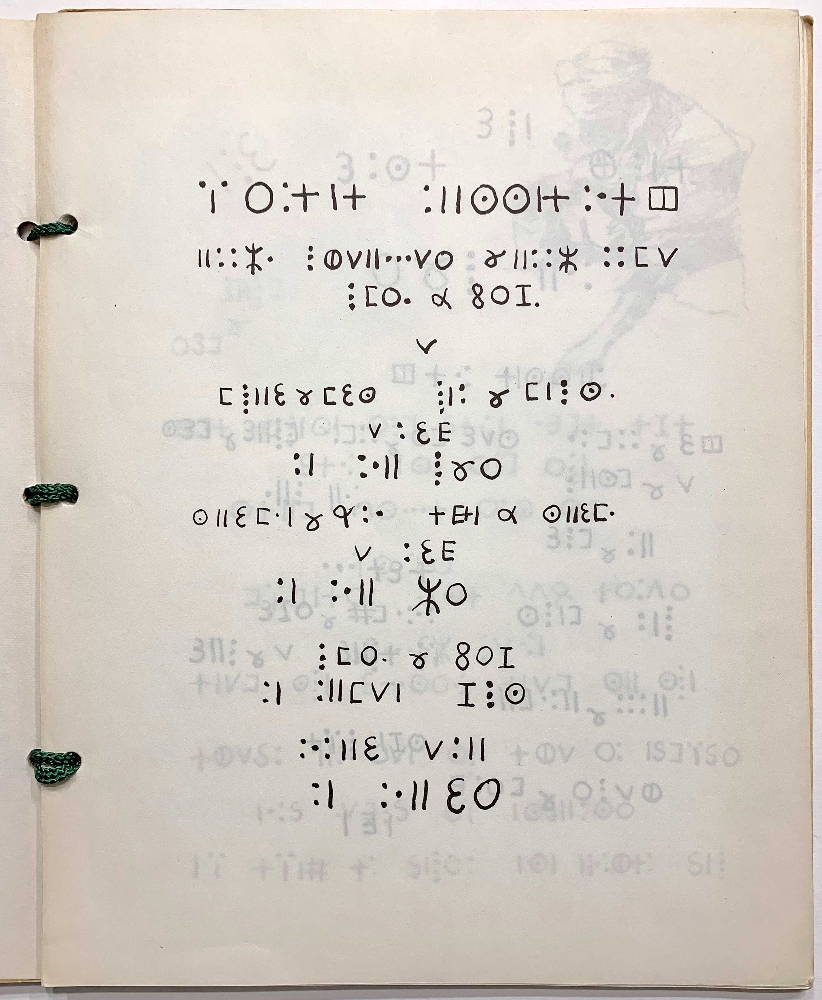

In the Sahara, the Tuareg people maintained their ancestral Tifinagh script, often used in personal letters, symbolic markings, and artistic decoration. Unlike Arabic or French, which dominated administration.

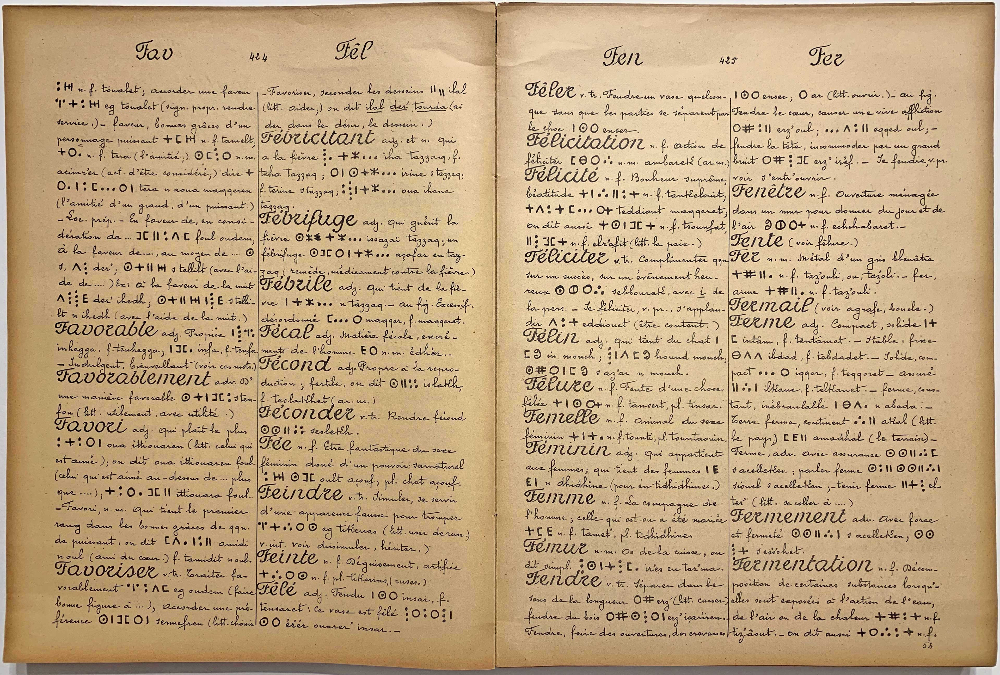

Page 424-425 - Tuareg language dictionary

by Said Cid Kaoui, 1894

The first actual Tuareg literature printed in Tifinagh script

was this little known late 1950s

Tifinagh served as a discreet form of expression and identity, with women especially playing a central role in transmitting the script through jewelry, textiles, and inscriptions. This ensured its continuity as a living cultural practice, even when marginalized by the colonial state.

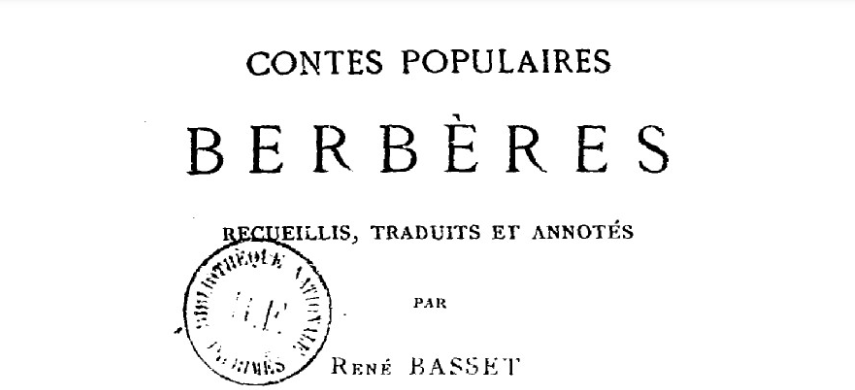

French scholars and administrators also contributed to the preservation—though often through an outsider’s lens—by documenting Amazigh languages. Linguists such as René and André Basset, along with intellectuals like Mouloud Mammeri and Mouloud Feraoun, transcribed oral poetry, compiled grammars, and published collections.

Amazigh literature translated and annotated

by René Basset, 1887

These works, usually in Latin transcription, represented the first systematic academic attempts to study Amazigh literature, even if they reflected colonial interests.

Mouloud Mammeri

At the same time, writing became a tool of resistance. Some Amazigh poetry composed in Arabic script carried subtle anti-colonial messages, criticizing occupation and preserving collective memory (like Moufdi Zakaria).

Moufdi Zakaria

While French authorities privileged French in official use, Amazigh communities kept their voices alive through manuscripts, oral recitations, and script traditions.

Thus, the colonial period was not one of silence, but of adaptation, survival, and the preparation for the Amazigh cultural revival that would follow in the post-independence era.

Reclaiming the Written Heritage Today

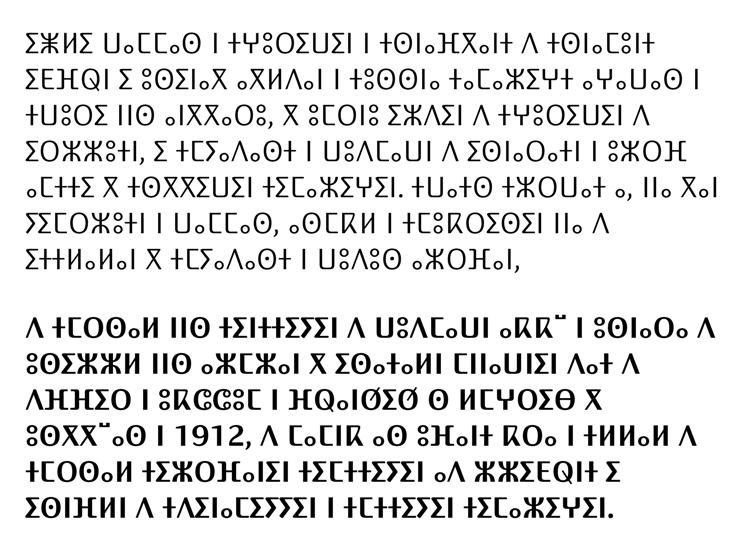

In modern times, Amazigh communities across North Africa are actively reviving their scripts and literary traditions. The most visible symbol of this renaissance is Neo-Tifinagh, a standardized version of the ancient alphabet now taught in schools, displayed on public signage, and celebrated in media. Morocco, Algeria, and beyond have integrated Tifinagh into cultural institutions, affirming Amazigh identity within national narratives.

An example of a Amazigh Text from a Schoolbook (Morocco)

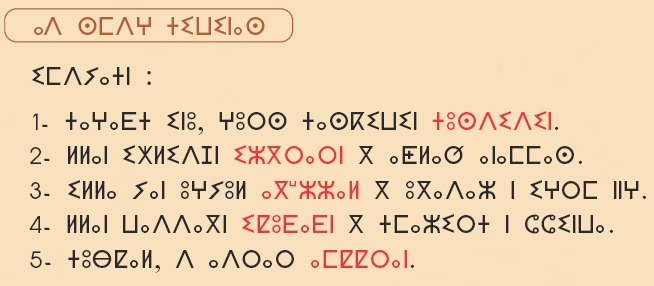

Artists and activists use Tifinagh not only as a tool of communication but as an emblem of pride—painting it on murals, calligraphy art, printing it on clothing, and embedding it in digital platforms.

Calligraphy using Tifinagh

Linguists and cultural organizations are also working to digitize ancient inscriptions and preserve medieval manuscripts, bridging the past with the future. For many young Amazigh, writing in Tifinagh is both an act of cultural memory and a declaration of presence in the modern world.

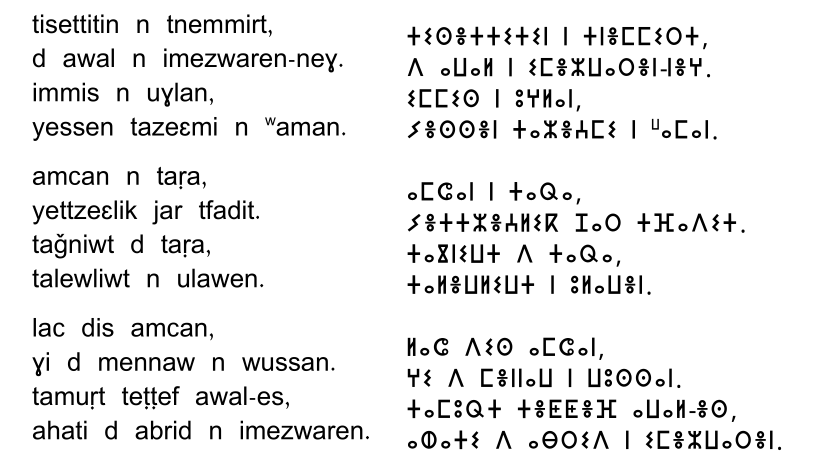

Modern Tifinagh Script

Piece of Mozabite poem written in

Modern Tifinagh Script and Latin Script

Conclusion

The story of Amazigh writing is not a closed chapter of history but a continuing dialogue across centuries. From silent stone inscriptions to vibrant street art, from royal declarations to everyday digital messages, the Amazigh script has adapted and endured.

What was once carved into desert rock now glows on computer screens, reminding the world that identity inscribed long ago can still guide a people’s future.

Tifinagh Alphabet – the traditional Amazigh Script