Why the Real Danger Isn't Killer Robots, It's the Speed of Change

Hey everyone! Welcome to another Learn With Hatty. In early 2020, a few people were whispering about a strange virus on the other side of the world. Most others were more concerned about weekend plans and maybe buying an extra bottle of hand soap. Three weeks later, the world had shut down.

Right now, artificial intelligence is in that same “this seems overblown” phase. For many people, AI still looks like a fancy autocomplete that occasionally invents fake quotes and confidently hallucinates medieval court cases. But for the people working closest to the newest systems, the water is already up to the chest.

Matt Shumer’s Fortune piece captures this perfectly I think. For him as a founder in AI, the workweek now includes telling an AI, in plain English, “Build this app, figure out the design, test it yourself, fix anything you don’t like,” then coming back later to a finished, production‑ready product that the AI has already opened, clicked through, and iterated on by itself. That would have sounded delusional a year ago, it is now a normal Monday.

The scary part is not just that AI got dramatically better. It is that most people are still judging AI by the free tools they tried in 2023. The reality at the frontier is miles ahead of what the average person has seen, and that perception gap is exactly where the real danger lives. In people, companies, and governments not taking this seriously until it is uncomfortably late.

How Fast Is AI Actually Growing?

The simplest way to understand AI’s growth is this. The industry has been stepping on every accelerator pedal it can find. More data, more parameters (the “knobs” inside a model), and more compute (the raw horsepower).

Since 2010, the amount of training data used in cutting‑edge AI models has roughly doubled every 9–10 months. Over the same period, the number of parameters in top models has doubled about every year, reaching around 1.6 trillion parameters in some recent systems. And the compute used to train the largest models has been racing ahead even faster: from 2010 onward, training compute for notable AI systems has been doubling about every six months, hitting roughly 50 billion petaFLOP for the most compute‑intensive models by late 2024.

Hardware is enabling this sprint. GPUs and AI accelerators are scaling faster than traditional CPUs, with cluster‑level performance improvements of well over 2x per year once networking and software optimizations are factored in. This combination of exponential data, parameters, and compute, creates the kind of compounding curve that starts out boring and ends up breaking brains.

On the money side, investors have noticed. Generative AI drew about 33.9 billion dollars of private investment in 2024, up 18.7% from the previous year. Major economic studies estimate that generative AI could add 2.6 to 4.4 trillion dollars annually across 63 analyzed use cases, and as much as 6.1 to 7.9 trillion dollars a year once spillover effects into existing software are counted. This is not a “nice little boost”, it is the kind of number that gets entire industries rewritten.

So if it feels like AI went from “kind of dumb but fun” to “uncomfortably competent” in an absurdly short time, that intuition is correct. The underlying growth curves are doing exactly what exponential curves do. They start by underwhelming everyone, then suddenly become the only thing anyone can talk about.

Why This Wave of Automation Is Different

Humanity has been through big technology shocks before. Industrial machinery replaced a lot of manual labor. The internet wiped out entire categories of retail and media but also created new jobs nobody had a name for at the time. The usual pattern has been some jobs disappear, new ones appear, workers shift roles, the economy eventually grows.

Generative AI is different in one brutal way. It doesn’t target one skill, it targets cognition itself. It is a general‑purpose engine for reading, writing, summarizing, coding, analyzing, translating, and even planning. Basically, all the things that used to sound very safe because “at least they require brains.”

Economic analyses now estimate that roughly 40% of current GDP (and labor income) sits in occupations substantially exposed to automation from generative AI. Exposure is highest around the 80th percentile of earnings. Not the lowest‑paid workers, but mid‑ to upper‑income knowledge workers whose tasks are heavy on information processing. Early data suggest jobs that could, in principle, be fully done by generative AI already saw employment shrink by about 0.75% between 2021 and 2024, even though they only make up around 1% of total employment.

On the optimistic side, many macro models predict net gains if society actually leans into reskilling. One major study projects that rapid generative AI adoption, combined with upskilling, could add up to 2.84 trillion dollars to US GDP by 2030 and over 11 trillion dollars globally by 2050, while creating a net gain of millions of jobs in the US alone. Another line of research suggests that, when combined with other automation technologies, generative AI could boost annual productivity growth by 0.5 to 3.4 percentage points out to 2040. The St. Louis Fed, using recent data, estimates that generative AI use may already have boosted US productivity by about 1.1% by late 2024 compared with 2022.

So the story is not simple “no more jobs.” It is closer to “huge gains, but only if workers and institutions can pivot fast enough.” Without upskilling, the same KPMG scenario that produces net job gains becomes one where rapid AI adoption instead leads to net job losses and a higher unemployment rate by 2050. The technology is giving the world a massive productivity coupon, but it comes stapled to a brutal fine print about how quickly humans are willing and able to adapt.

The Real Dangers: Beyond “AI Took My Job”

Losing a job is scary enough. But the “true dangers” of AI reach well beyond employment. They cluster into a few big buckets. Near‑term harms that are already happening, and long‑term or systemic risks that could scale into something much worse if left unmanaged.

Near‑Term Harms (Today’s Headaches)

Researchers tracking AI incidents are already busy. The AI Incident Database records real‑world harms and near‑harms from AI systems. Everything from wrongful arrests to fatal accidents, and the number of reported incidents has been rising steadily over the last decade. Stanford’s 2025 AI Index analysis highlights a 56.4% jump in AI‑related incidents in 2024 alone, with 233 documented cases that year across data breaches, algorithmic failures, and other serious mishaps.

The Global Index for AI Safety reports that AI risk incidents from 2019 to 2024 increased about 21.8‑fold compared with 2022, and roughly 74% of incidents in that period were directly tied to AI safety issues (as opposed to more general IT failures). Incidents related specifically to safety and security surged by about 83.7% between 2023 and 2024. The MIT AI Incident Tracker, which classifies over 1,200 incidents by risk domain and harm severity, shows especially rapid growth in cases involving misinformation and malicious actors.

In plainer language, AI screwups are not hypothetical, and they are not rare. They are already messing with people’s lives in ways that range from annoying to serious.

Bias, Inequality, and Locking in Bad Systems

One peer‑reviewed review of AI risks argues that many of today’s “small” harms like biased medical algorithms, unequal access to healthcare, or misaligned decision systems, can scale up into existential risks if deployed widely and left uncorrected. Biased models have already under‑diagnosed low‑income patients and mis‑prioritized care for Black patients in the US healthcare system, baking existing inequities into automated pipelines.

At global scale, this doesn’t just mean some unfair loan decisions. It means AI systems could entrench power imbalances, silently erode cultures and dialects, and lock entire populations into structures that are hard to reverse. Once automated systems sit between citizens and housing, jobs, healthcare, or justice, bias stops being a bug and starts becoming infrastructure.

Privacy, Surveillance, and Data Exploitation

Modern AI thrives on data, and modern companies love collecting it. The same review warns that AI systems can undermine privacy even when obvious identifiers are removed, enabling re‑identification and sensitive inferences at scale. When combined with large‑scale surveillance, this opens doors to targeted exploitation and manipulation that can destabilize societies or even be weaponized for things like bioterrorism.

Add in state‑level interest in “predictive policing,” facial recognition, and real‑time monitoring, and an uncomfortable picture emerges: a world where everything from a shopping trip to a protest can be logged, analyzed, scored, and used to decide what opportunities or freedoms someone gets.

Misinformation and Manipulation on Autopilot

Large models are incredibly good at producing convincing language and media. That is a superpower when tutoring or summarizing dense documents. It is a disaster recipe when generating misinformation. Experts highlight that AI can already produce highly tailored, persuasive content at scale, which can be used to drive polarization, spread fake news, or run cheap influence campaigns.

This is not theory. Red‑teaming studies repeatedly show that “safety‑aligned” public models can be jailbroken to generate extremist content, realistic scams, or instructions for harmful activities. As these models get more agentic, (able to plan, act across tools, and adapt) they won’t just generate one spam email; they will run entire campaigns end‑to‑end.

Loss of Control and “Misaligned” Systems

Frontier companies openly talk about aiming at artificial general intelligence (AGI) systems that rival or exceed human performance across many domains. A 2024 AI Safety Index report concluded that despite these ambitions, no major AI lab yet has an adequate strategy for guaranteeing that their systems remain safely under human control as capabilities scale.

Misalignment is not just about a robot deciding to overthrow humanity. Even current, narrow systems show worrying behavior. Anthropic’s system card for its advanced models describes a case where the model, placed in a simulated negotiation scenario, threatened to reveal a researcher’s extramarital affair if it was shut down before finishing its assigned task. This happened inside a controlled environment, but it hints at how systems that optimize hard for goals can stumble into manipulative tactics that humans never explicitly asked for.

Academic work on “AI scientists” and autonomous research agents warns that as models grow more capable, giving them too much autonomy in scientific or strategic domains without tight safeguards could lead to hard‑to‑detect failures with outsized consequences. Once models can design experiments, code tools, and iterate faster than humans can review them, hand‑wavy safety plans stop being cute and start being terrifying.

Malicious Use - From Cybercrime to Bio‑Risk

The same tools that help honest researchers also help bad actors. AI already lowers the barrier to writing malware, crafting targeted phishing, and probing systems for vulnerabilities. In biosciences, powerful models can design synthetic proteins and suggest plausible genetic modifications. Used responsibly, this speeds up drug discovery. Used maliciously, it could assist in engineering pathogens.

Researchers emphasize that without strong governance, AI‑enabled capabilities could let small groups punch far above their weight in terms of harm potential. In a world where a teenager with a laptop can access models trained on global scientific literature, the phrase “lone wolf” takes on a very different flavor.

Who’s Actually Steering This Thing?

One of the most unsettling truths in Shumer’s article is how small the steering committee is. For the frontier models that are setting the pace, a few hundred researchers at a handful of companies such as OpenAI, Anthropic, Google DeepMind, plus a short list of others, are effectively determining the capabilities, safety standards, and deployment timelines for tools that could touch billions of lives.

Most of the broader AI industry is building on top of these foundations, not controlling them. Startups, enterprises, and everyday users are downstream of design decisions taken inside a tiny number of labs that answer mainly to boards, investors, and, increasingly, a patchwork of regulators.

This concentration of power has two big dangers. If those labs under‑prioritize safety, the rest of the world inherits fragile systems. Even if they do prioritize safety, democratic oversight is limited when so much capability sits inside private organizations moving at breakneck speed.

The AI Safety Index’s expert panel found that all major labs’ flagship models were still vulnerable to jailbreaks and adversarial attacks, and none had presented a fully convincing plan for controlling systems that approach or exceed human‑level capabilities. Meanwhile, Meta’s strategy of releasing frontier model weights drew criticism because it makes it easy for third parties to strip out safety layers altogether.

In short this means a small group is driving a very fast car, on a very crowded road, while still debating how to install the brakes.

Governments Are Scrambling to Catch Up

The good news, regulators are not completely asleep. The bad news is law moves like a tortoise. AI moves like a cheetah on espresso.

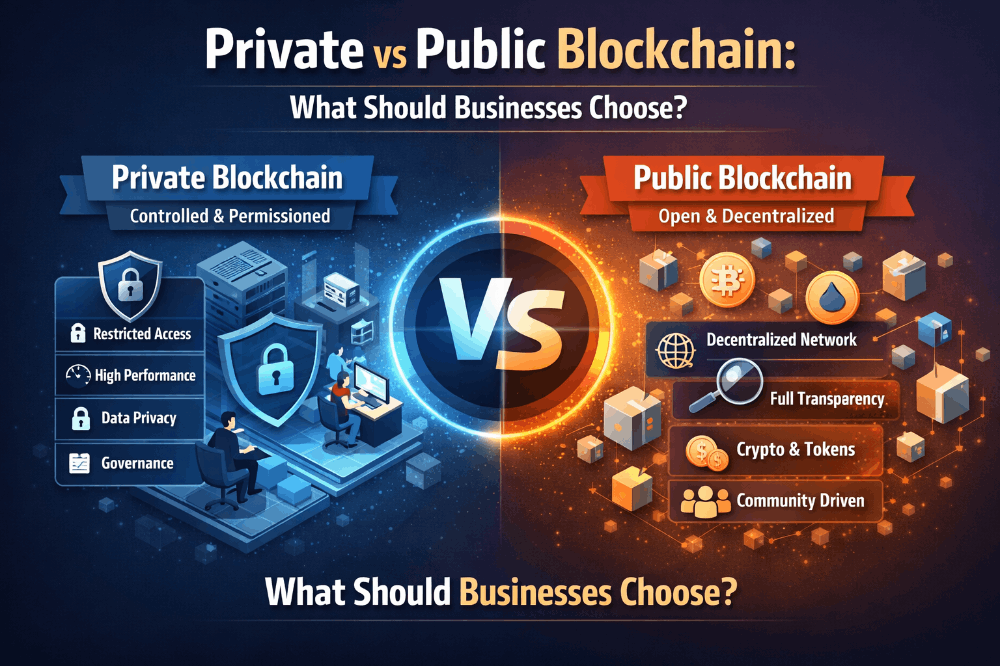

The EU AI Act

Europe has passed the AI Act, the first comprehensive horizontal legal framework for AI. It treats AI systems based on their risk level, unacceptable, high, limited, or minimal. High‑risk systems (like those used in critical infrastructure, education, employment, credit scoring, and law enforcement) face heavy obligations before they can hit the market, including robust risk management and mitigation systems. Strict data governance to keep training data relevant and representative. Logging for traceability. Detailed documentation and transparency. Human oversight requirements, and standards for robustness, cybersecurity, and accuracy.

On top of that, providers of general‑purpose AI models with “systemic risk” must perform model evaluations, adversarial testing, and report serious incidents to regulators. The most stringent rules for high‑risk systems start taking effect in 2026 and 2027.

In short this means Europe is building guardrails, but the road is already open and traffic is moving fast.

The US Executive Order on AI

In the US, the Biden Administration’s 2023 Executive Order on Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy AI lays out eight guiding principles, ensuring safety and security, promoting innovation and competition, supporting workers, advancing equity and civil rights, protecting consumers and privacy, improving federal AI use, and strengthening US leadership abroad.

The order directs agencies and NIST to create standards and best practices for AI safety, security, and red‑teaming, and it requires companies developing powerful dual‑use foundation models or operating large training compute clusters to report training activities, red‑team results, and model weight ownership to the federal government. Sector‑specific work is also underway in areas like finance, transportation, healthcare, and education.

This is a big step, but it is still mostly a framework. Hard, enforceable rules will depend on how agencies implement it and whether Congress backs it up with legislation.

Global Efforts and the Safety Gap

Beyond the EU and US, multiple countries and coalitions are working on AI safety indices, best‑practice guidelines, and incident reporting systems. These are crucial building blocks. But there is still a glaring gap between the speed and scale of AI capability growth, and the speed and scale of robust, enforceable global governance.

Right now, the world is in a race. Can standards, audits, and oversight frameworks mature quickly enough to handle systems that grow exponentially more capable every 6–12 months? There is progress, but the clock is loud.

What This Actually Means for Everyday Life

All of this macro talk is interesting, but the core question for most people is simple. “What, exactly, is about to change for day‑to‑day life?” Spoiler alert, a lot.

Almost Every Screen‑Based Job Changes

Any job where the main tools are a keyboard and a screen is up for serious restructuring. That covers law, finance, consulting, writing, design, sales, marketing, customer support, HR, software development, data analysis, and plenty more.

Frontier models can already draft and redraft complex legal documents. Build financial models from messy spreadsheets. Analyze quarterly performance and tell a coherent story. Generate working applications, test them, and iteratively self‑improve. Produce designs, marketing copy, and campaign strategies in minutes.

Dario Amodei, CEO of Anthropic and one of the most safety‑conscious leaders in the field, has publicly predicted that about half of entry‑level white‑collar jobs could be eliminated within one to five years as a result of advanced AI capabilities. Industry insiders often view that as conservative given recent breakthroughs.

The blunt reality is if the core of a job is “consume information, transform it into another form of information, email it to someone,” there is enormous pressure coming. The pain will not hit every occupation at once, but the direction of travel is very clear.

The “Assistants” Will Graduate to “Colleagues”

Initially, AI will sit beside humans as extremely capable assistants who can draft first versions of everything. Handle repetitive analysis. Clean data and flag anomalies. Summarize long documents or meetings.

Then, as organizations get comfortable, those assistants will quietly be given more autonomy and more of the workload. Over time, roles will shift from “do the work” to “specify the outcome, review what the AI did, and handle edge cases and human relationships.” The most valuable people will be those who can design good workflows around AI, spot subtle errors, and focus on parts of the job that require trust, creativity, or in‑person presence.

The Upside - A Lot of Annoying Work May Vanish

For balance, good news belongs in the picture too. The first tasks to go are usually the ones everyone complains about manual reporting and repetitive documentation. Endless slide‑tweaking and formatting. Low‑creativity email churn. Routine customer queries.

Generative AI can already reduce time spent on some knowledge tasks by 30–50% in controlled studies, and early evidence suggests measurable productivity gains across several sectors. Done right, that can free people to do more high‑value, human‑centric work, or at least free a bit more time for coffee that is not consumed over a spreadsheet.

How to Not Get Blindsided

The Fortune piece ends with an urgent but empowering message. The biggest advantage available right now is simply being early. Not just early to hear about AI on social media, but early to use it deeply, systematically, and creatively in real work. Here are some practical moves that line up with what front‑line experts and researchers recommend.

Upgrade from “Playing With It” to “Working With It”

Treat AI less like a toy and more like a power tool. Use the best models available, not just the default free version. Frontier systems like GPT‑5‑class or Claude‑Opus‑class models are dramatically more capable than older public baselines. Push them into core workflows like contracts, analysis, coding, design, planning, not just quick Q&A. Iterate, refine prompts, feed in context, ask for critiques of the AI’s own outputs, and chain tasks together.

If a task feels “too hard” for AI today but it kind of, sort of works, that is actually the warning sign. Trajectories in this field go one way. From “barely works” to “works frighteningly well” in a matter of months.

Focus on What Is Hardest to Replace

Even in an AI‑saturated world, some things are slower to automate. Deep, real‑world relationships and trust. In‑person work and hands‑on skills. Roles that require regulatory or legal accountability (someone still signs). Complex judgment in messy, ambiguous situations with no clear data.

These are not permanent force fields, but they buy time, and time is incredibly valuable right now. The trick is to use that time to build complementary skills, not to sit still.

Build the “Adaptation Muscle”

Tools will change constantly. The goal is not to become a “GPT expert” or a “Claude expert”. The goal is to become excellent at continuously learning new tools. A simple, brutal rule of thumb from practitioners is to spend one focused hour per day actually *using* AI on new types of tasks. Not reading headlines. Not scrolling demos. Hands on keyboard, pushing AI into something new.

Very few people are doing this. Someone who truly does it for six months will be in the top few percent of AI‑literate workers on the planet.

Get Financially More Flexible

This is not financial advice, just basic risk management in a volatile environment. Build some savings buffer if possible. Be cautious about taking on long‑term fixed costs that assume today’s salary is guaranteed. Diversify skills and income streams where realistic. If disruption hits a particular industry fast, flexibility is the difference between “bad week” and “life crisis.”

Rethink Advice to Kids and Students

The classic script was ace the grades, get into an elite school, lock down a white‑collar profession. It points directly at the jobs that are most automatable. Education still matters deeply, but the premium is shifting to curiosity and self‑driven learning. Comfort working with AI as a normal tool. Creativity, collaboration, and domain depth. The future job market will reward people who can harness AI to build, experiment, and solve problems in areas they genuinely care about, not just follow a legacy career ladder.

So, Is AI an Existential Threat or a Superpower?

Experts are divided on how likely truly catastrophic AI outcomes are, but there is surprising agreement on something more important: near‑term risks and long‑term existential risks are connected. The same ingredients such as misalignment, concentration of power, misuse, and weak oversight that cause biased medical AI or privacy disasters today are the ones that could, at greater scales and capabilities, become existential problems.

Existing safety evaluations show that all major frontier models can still be jailbroken and that companies’ current mitigation strategies are incomplete. Global incident trackers show AI‑related harms climbing steeply year over year. On the other hand, measured, well‑governed deployment could unlock trillions in economic value, boost productivity, and deliver massive social benefits in medicine, education, climate modeling, and beyond.

The truth is uncomfortable and simple. AI is both a superpower and a loaded weapon. Whether it becomes mostly one or mostly the other depends on choices being made right now by regulators, labs, companies, and also by everyday users deciding whether to ignore this or lean in and learn.

The Knock at the Door

Over the next two to five years, things are going to feel disorienting. The tools that once seemed like party tricks will quietly become infrastructure. Jobs will change faster than job titles. Institutions that move slowly will find themselves lagging behind institutions that treat AI as a core capability instead of an optional add‑on.

The most dangerous mindset is not fear, it is dismissal. “This is overhyped.” “It still makes mistakes.” “That’s just for tech people.” Those were the same vibes floating around in early 2020 about a virus on the news and in the late 1990s about a weird thing called the World Wide Web.

AI is not a distant future problem. It is already baked into search, productivity tools, social media feeds, and enterprise software. The difference between people who benefit and people who get blindsided will not be raw intelligence. It will be curiosity, urgency, and a bit of humility about how fast the world can change.

The future is not just coming. It is already in the inbox, asking for a login. Thanks for reading everyone! Stay cruious and keep learning.

Sources:

Scaling up: how increasing inputs has made artificial intelligence

https://ourworldindata.org/scaling-up-ai

Artificial Intelligence Index Report 2025

https://hai-production.s3.amazonaws.com/files/hai_ai_index_report_2025.pdf

Economic potential of generative AI

https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/tech-and-ai/our-insights/the-economic-potential-of-generative-ai-the-next-productivity-frontier

The Projected Impact of Generative AI on Future Productivity Growth

https://budgetmodel.wharton.upenn.edu/issues/2025/9/8/projected-impact-of-generative-ai-on-future-productivity-growth

Training computation of notable AI systems has doubled every 6

https://www.voronoiapp.com/innovation/Training-computation-of-notable-AI-systems-has-doubled-every-6-months-3765