Does 'zombie deer disease' pose risks for humans?

Recent instances of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) in humans have sparked speculation about the possibility of a disease carried by deer crossing the species barrier.

Recent instances of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) in humans have sparked speculation about the possibility of a disease carried by deer crossing the species barrier.

Known as "zombie deer disease," chronic wasting disease (CWD) is a type of prion disease that affects wildlife, particularly deer. Cases have been reported in deer and moose in Canada, as well as in Yellowstone National Park in the United States.

While no confirmed cases of CWD in humans exist, a recent medical report from Texas, US, highlighted the deaths of two hunters who regularly consumed meat from CWD-infected deer. Both individuals died from CJD, although a definitive link to CWD could not be established. This has prompted calls for increased surveillance and research to determine the potential for CWD transmission to humans.

Experts express concerns about the increasing transmission of CWD among animals in various regions, including North America, Scandinavia, and South Korea. They cite experimental studies, historical instances of prion diseases crossing from animals to humans (though extremely rare), and the potential impacts of climate change as reasons for heightened vigilance regarding the risk of transmission to humans.

According to Jennifer Mullinax, an associate professor of wildlife ecology and management at the University of Maryland, there have been no reported cases of transmission from deer or elk to humans. Nevertheless, due to the potential risks associated with prion diseases, organizations like the CDC and others have advocated for measures to prevent any prion disease from entering the food chain.

What is zombie deer disease and what are the symptoms?

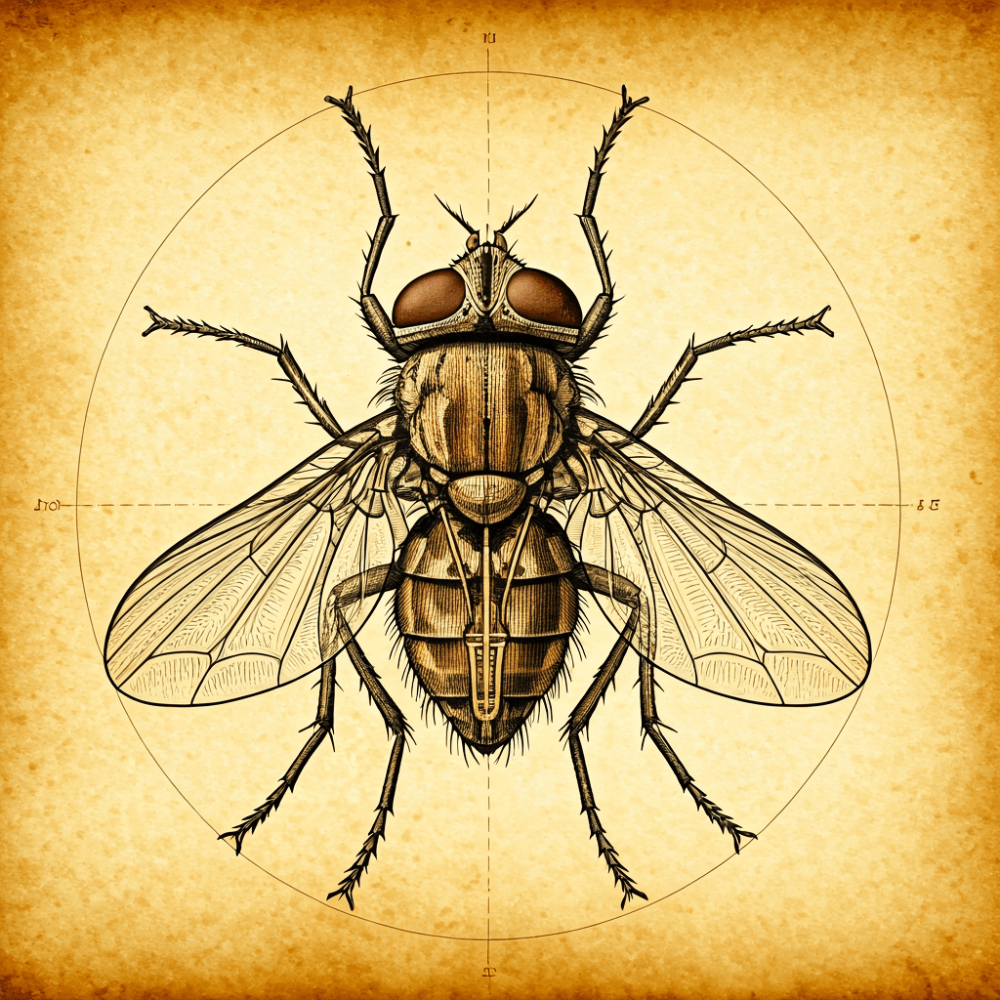

Chronic wasting disease (CWD) is a contagious illness found in cervids, which are hoofed ruminant mammals like deer, reindeer, elk, and moose. Unlike bacterial or viral infections, CWD is caused by a misfolded prion protein, as stated by the US Department of Agriculture's Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service.

The exact cause of the abnormal folding of the prion protein is not yet fully understood by researchers. Normally, prion proteins may play a role in cellular signaling, but when they become misfolded, they induce other proteins to misfold as well.

In the brain, misfolded prion proteins lead to the death of brain cells and subsequent bodily dysfunction, resulting in peculiar symptoms. These symptoms include weight loss, increased drinking and urination, impaired balance and coordination, drooping ears, and difficulty swallowing. The difficulty in swallowing may result in drooling and, ultimately, complications like pneumonia and death. These distinctive symptoms, along with the image of an uncoordinated, stumbling, and drooling animal, have given rise to the term "zombie deer disease." Since the symptoms can take months or even years to appear, visual diagnosis can be challenging.

Can zombie deer disease spread to humans?

According to the CDC, infection rates of chronic wasting disease (CWD) in areas where the prion disease is endemic range from 10% to 25%. Surveillance results from the Canadian province of Alberta in 2023 suggest a 23% positivity rate for mule deer.

Current evidence does not support the transmission of CWD to humans through consuming infected animal meat, encountering infected wildlife, or contacting contaminated soil or water. However, researchers are actively investigating the possibility of animal-to-human transmission. Jennifer Mullinax states that the current research findings are inconclusive.

Earlier research from the CDC, published in 2011, utilized the Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network 2006-2007 population survey, involving over 17,000 participants.

Despite more than 65% of respondents reporting consuming wild game, the study found no evidence of human transmission of CWD.

Prion diseases, including Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (CJD) and variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (vCJD), affect humans. vCJD is confirmed to be caused by the same infectious agent as bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), or "mad cow" disease. However, Michael Osterholm emphasizes that the structural differences between BSE and CWD prions make it uncertain whether CWD transmission to humans would lead to similar pathology and clinical presentation.

In a 2004 study, CDC researchers examined CJD cases in Wyoming and Colorado from 1979 to 2000, where CWD was first detected in 1967. While the incidence of CJD in these states was similar to the rest of the United States, only two non-familial cases of CJD in individuals who consumed venison in endemic areas had been reported. Although CJD was previously transmitted through medical procedures, such cases have not been reported since improved sterilization procedures were implemented in the mid-1970s, according to the CDC.

What experimental studies of chronic wasting disease show

Jennifer Mullinax highlights that laboratory and animal-based testing regarding the transmission of chronic wasting disease (CWD) has yielded varied outcomes depending on the species and methodologies employed. Each species possesses a distinct level of resistance or susceptibility to CWD prions, with species more closely related to humans exhibiting complete resistance.

A 2018 study by the National Institutes of Health involved exposing 14 macaques, sharing approximately 93% of their genome with humans, to CWD-infected brain tissue from deer and elk. Despite monitoring the macaques for over a decade and conducting various tissue tests, researchers found no evidence of transmission from the infected cervid tissue to the macaques. However, unpublished experimental research has suggested potential transmission from cervids to macaques.

In a 2022 experimental study by the University of Calgary, CWD isolates from infected deer were injected into "humanized" mice, genetically modified to mimic human diseases. Over 2.5 years, the mice developed CWD and excreted infectious prion proteins in their waste. The study indicated the development of an atypical prion signature in the mice, suggesting that if CWD were transmissible to humans, it might present with atypical symptoms, complicating diagnosis. The study also raised concerns about fecal shedding in the mice, highlighting the potential for infected individuals to spread the disease to others.

Michael Osterholm notes inherent limitations in these studies, which complicate the interpretation of results. While recent scientific publications provide insights, there is insufficient evidence to definitively conclude whether CWD can breach the species barrier.

What's being done about surveillance of chronic wasting disease?

CIDRAP has convened a panel of experts to develop a contingency plan in case chronic wasting disease (CWD) were to cross over to humans, actively monitoring the risk. Meanwhile, researchers at the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine's Wildlife Futures Program are studying the gut microbiota of both non-infected and CWD-infected deer to enhance surveillance and gain insights into the disease.

Efforts are underway to develop potential live tests for CWD, which could significantly aid in preventing humans from consuming infected deer, according to Jennifer Mullinax. Additionally, ongoing research aims to understand how CWD prions might mutate and potentially affect various animal species, including humans.

Experts express concerns about the potential for CWD to evolve over time, with ongoing transmission in cervids possibly leading to the emergence of novel CWD prion strains capable of infecting different hosts, as highlighted by Michael Osterholm.

Furthermore, the impact of climate change is a factor of concern. Research indicates that deer populations may increase in response to climate change, potentially influencing the spread of CWD, as noted by Jennifer Mullinax.