When Speaking Is Not Using: The Impasse of InfoFi

When Speaking Is Not Using: The Impasse of InfoFi

The crypto world often presents itself as a promised land of abundance: the realm of internet magic money, where a well-executed trade can change lives. Even for those without capital to invest, it is a universe known for airdrops, usage incentives, and promises of accessible gains. In this context, InfoFi appears, at first glance, as a coherent strategy.

Still, it is necessary to begin with the obvious, however uncomfortable: do these campaigns meaningfully alter the real use of protocols? Do they produce adoption, or merely discursive circulation? When we observe the flood of repetitive content and AI-generated slop, the answer tends to be negative. Intense movement at the level of language does not necessarily translate into practical displacement. What is often called traction is, most of the time, nothing more than surface occupation.

InfoFi is born from a seductive hypothesis: if information has value, then informational engagement should be rewarded. In an ecosystem accustomed to converting almost any behavior into economic incentive, the idea seems consistent. The error, however, lies in the basic premise: confusing language with use, visibility with experience, speech with commitment.

A brief historical detour

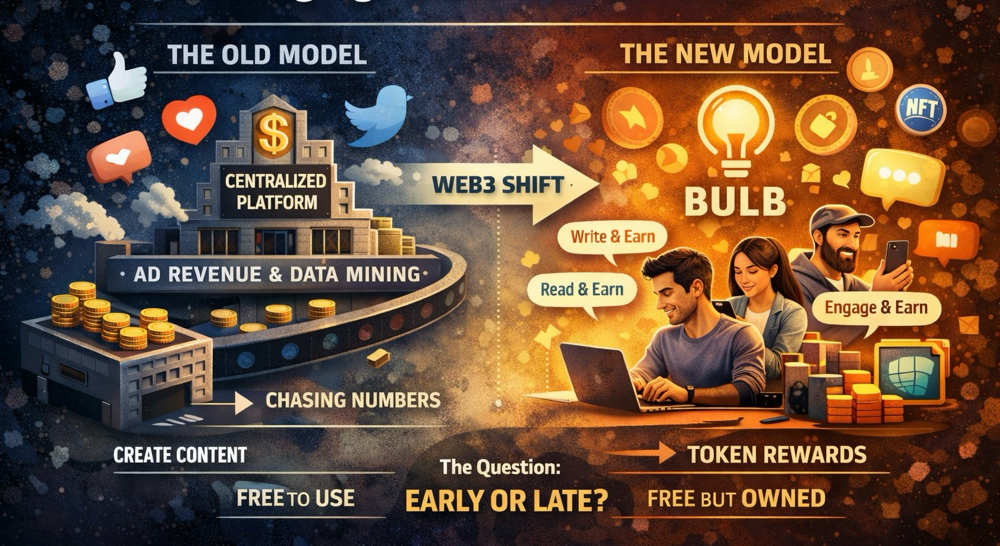

Before InfoFi, there was SocialFi. Before that, the classic platform model: engagement as metric, attention as resource, data as product. InfoFi does not break with this logic, it renders it financially explicit.

By directly monetizing discourse, the system removes the last remaining friction separating speech from real interest. Language adapts to the environment: faster, more generic, more replicable. AI merely accelerates a process already embedded in the design itself. The result, consequently, is not adoption but informational saturation with low pragmatic density.

To understand the present moment, and the abrupt interruption of several InfoFi platforms, it is necessary to step back a few years and observe how the direct monetization of language has been tested and repeatedly strained within crypto-social networks.

One of the most emblematic cases is Steemit, launched in 2016. The proposal is simple and radical: users are rewarded in STEEM tokens for publishing, commenting on, and curating content. At its initial peak, the platform surpasses one million registered accounts and distributes millions of dollars per month in tokens.

Subsequent empirical analyses, based on more than 500 million operations carried out by approximately 1.1 million accounts, reveal a telling pattern: over 16% of token transfers concentrate in automated mechanisms or actors exploiting the incentive logic rather than producing substantive content. The system generates intense transactional activity, but not durable communities, consistent retention, or deeper engagement with the platform itself. One detail becomes clear: the currency of exchange is not experience, but the exploitation of rules.

This dynamic anticipates, historically, what is observed today in InfoFi campaigns: a great deal of visible movement in metrics, little concrete transformation in adoption and real use.

Other attempts seek to correct parts of this problem. Platforms such as Minds, launched in 2015, combine discourses of freedom and privacy with more moderate tokenized rewards, reaching millions of users over time. Even so, the fragility persists: rewarded engagement functions as initial attraction, not as a structure of permanence. The pattern begins to crystallize, rewarding generates circulation, sustaining use requires friction and functional value.

In 2023, experiments such as Friend.tech introduce an explicitly financial layer to sociability: profiles turned into assets, social access priced, direct speculation over relationships. Initial growth is explosive, with tens of thousands of daily active users and high fee volumes. Retention, however, collapses just as quickly. When incentives diminish, use dissipates. The central point is not the peak, but the inability to sustain activity without direct reward.

The transition to InfoFi

With new projects emerging continuously and a permanent dispute for attention and adhesion, InfoFi once again appears promising. A new generation of platforms begins to monetize not only the post itself, but attention, reputation, discursive positioning, and narrative circulation.

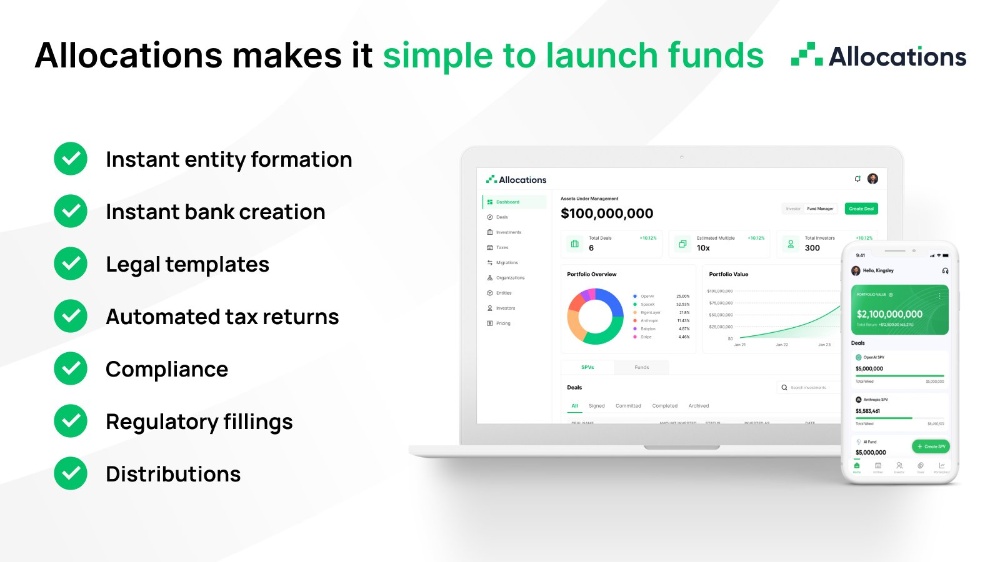

Platforms such as Kaito, Wallchain, Xeet, and Cookie DAO operate within this regime. The numbers are expressive: dashboards monitoring thousands of accounts, campaigns with high reply volumes, real-time mindshare metrics. The problem is that these metrics measure discursive intensity, not protocol use. There is no consistent evidence of correlation between InfoFi campaigns and sustained increases in active dApp users, long-term retention, or functional product integration. Discourse grows faster than experience.

What distinguishes the present moment is scale. With the consolidation of generative AI, automated replies, and algorithmic coordination, the distance between incentivized speech and human experience becomes structural. The volume of produced utterances exceeds platforms’ capacity to interpret them as legitimate interaction signals. What was once tolerable noise becomes operational and cognitive cost.

In this context, Cookie DAO’s announcement of the shutdown of Snaps gains analytical relevance. Even while operating within the rules, with official data and legitimate access, the model proves incompatible with the new framing. There is no moral accusation, there is structural exhaustion. InfoFi becomes epistemologically too expensive: producing, filtering, and validating meaning requires more energy than the system can justify.

The energy dilemma

The tightening of X’s API policies is not merely a technical adjustment. It functions as an energy cut. Suddenly, much of InfoFi discovers it is plugged into a socket it does not control. When the flow is interrupted, the system does not slow down—it simply shuts off.

Projects such as Cookie DAO and Kaito recognize this limit by discontinuing features tied to direct engagement rewards. More revealing than market reaction is the exposure of a structural risk: dependence on Web2 APIs to sustain tokenized growth loops. InfoFi outsources its energy, and outsourced energy tends to be provisional.

In the race to position themselves amid the crisis, Kaito’s response is perhaps the most illuminating of the cycle. Not because it ends a product, but because it abandons an imaginary. By announcing the sunset of Yaps and incentivized leaderboards, Kaito does not propose incremental adjustments, it assumes the model is no longer compatible with the future it intends to build.

The decisive point of the announcement is not operational but conceptual. The question shifts from “how can we improve the system?” to “is this still the right system?”. Yaps embodies the classic Web3 ethos: open access, permissionless distribution, merit measured by visible participation, functioning as a driver of awareness and global expansion, onboarding hundreds of thousands of new users into crypto.

Over time, however, it becomes clear that the problem is not refinement. Stricter filters, additional criteria, and signal combinations do not resolve the noise. Spam ceases to be understood as deviation and is recognized as an emergent property of the design of consumption and creation within social networks, intensified by creative automation and X’s algorithmic changes.

Perhaps the most relevant aspect of Kaito’s position is its reading of crypto’s future. The idea of a universal ownership economy does not materialize. The central opportunity becomes operating as invisible infrastructure for payments, stablecoins, tokenization, and global markets.

Platforms that still make sense

If the collapse of InfoFi exposes the limits of direct posting incentives, it also illuminates which architectures may still traverse this moment, not because they are immune, but because they operate under different regimes of energy, time, and value.

Rally’s response, for instance, does not deny the collapse, it incorporates it. By abandoning mindshare logic and adopting granular campaigns, it shifts the focus from emission to validation. Participation ceases to be automatic. AI does not disappear, but it loses its marginal advantage.

In an environment dominated by fast, viral content, platforms such as BULB follow another path. By prioritizing writing, reading, and permanence, time becomes a filter. AI can produce quickly, but it cannot sustain attention. Growth is slower, less spectacular, but structurally more stable.

A sector in transition

What takes shape after the shock imposed by X is not directly the end of InfoFi, but the closure of an expansive model grounded in cheap energy and abundant language. The platforms that remain standing are those that begin to redesign their circuits: reducing dependence on central APIs, shifting incentives from emission to consequence, and treating volume not as virtue, but as a cost to be managed.

Within this new framing, AI does not disappear; it reconfigures. Where logic still privileges speed, repetition, and immediate response, automation dominates. Where friction, time, validation, and context emerge, AI loses centrality and becomes just another agent.

Perhaps this is the real turn: leaving behind the obsession with scaling discourse and beginning to care for the ecology in which discourse takes place. No longer growing at any cost, but learning how to sustain.