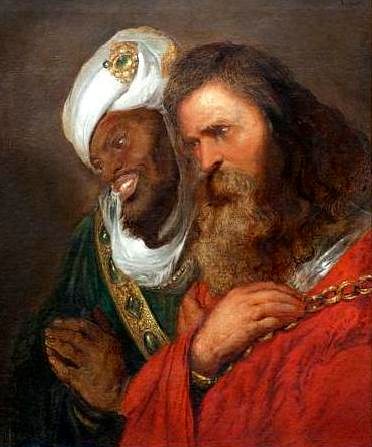

CONQUEROR OF JERUSALEM: SELAHADDIN AYYUBI

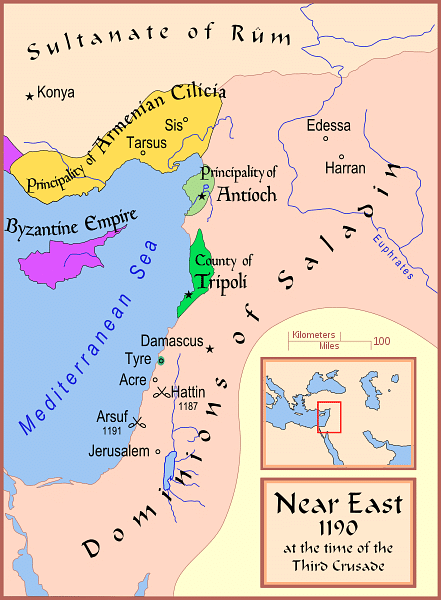

Saladin (1137-93) was the Muslim Sultan of Egypt and Syria (1174-1193) who shocked the western world by defeating an army of Christian Crusader states at the Battle of Hattin and then capturing Jerusalem in 1187. He destroyed the Latin Eastern states in the Levant and successfully repelled the Third Crusade (1187-1192).

Saladin achieved his success by uniting the Muslim Near East from Egypt to Arabia with a powerful combination of war, diplomacy and the promise of holy war. Saladin's prowess in war and politics, as well as his personal qualities of generosity and chivalry, were praised by both Christian and Muslim writers, so that he became one of the most famous figures of the Middle Ages, the subject of countless literary works since his death in 1193 in his favorite gardens of Damascus. happened.

Early Career

Saladin Ayyubi, whose full name was al-Malik al-Nasir Selah al-Dunya wa'l-Din Ebu'l Muzaffer, Yusuf Ibn Ayyub Ibn Shadi al-Kurdi, son of Ayyub, a displaced Kurdish mercenary, from Tikrit, north of Baghdad He was born in the Castle in 1137. Saladin would rise through the ranks of the army, where he gained fame as a skilled horseman and a skilled polo player. Saladin followed his uncle Shirkuh during the expedition that conquered Egypt in 1169. Later, Saladin took over the governorship of Egypt from his relative for Nureddin (sometimes given as Nur'el-din) (1146-1174), who became the independent governor of Aleppo and Edessa. Historian J. Phillips gives the following succinct description of the young Saladin:

...a short man, with a round face, a thin black beard and sharp, watchful black eyes. He placed members of his family in positions of power and appeared to challenge his master's authority.

When Nureddin died in May 1174, his coalition of Muslim states disintegrated as his successors fought for supremacy. Saladin claimed himself as the rightful heir and took Egypt for himself.

Uniting the Islamic World

Saladin, now Sultan of Egypt, repeated Nureddin's victory in Syria with the capture of Damascus in 1174. Saladin declared himself the protector of Sunni Orthodoxy, and his removal of the Shiite caliph in Cairo and the organization of his state under strict Islamic law gave serious weight to this claim. Saladin then began to unite the Muslim world, or at least form some sort of beneficial coalition—no easy task, given the differences in religious beliefs of Sunni and Shia Muslims, with many states, independent city administrators, and others.

Saladin's strategy was a powerful blend of warfare and diplomacy, mixed with the idea that he could wage a holy war against the Christian settlers who had established Latin states in the Middle East, such as the Kingdom of Jerusalem. First, the military leader also did not hesitate to declare war on his Muslim enemies. For example, in 1175, an army from his rival in Aleppo was defeated by him in Hama. Saladin's pre-eminence among Muslim leaders was reinforced when the Baghdad caliph, the head of the Sunni faith, officially recognized him as governor of Egypt, Syria, and Yemen. Unfortunately, Aleppo remained independent and was ruled by Nureddin's son, which was a serious issue on Saladin's diplomatic side. There were also more personal risks, as the Sultan of Egypt twice survived assassination attempts by the Assassins, a powerful Shiite sect. Saladin immediately responded by attacking the assassin-held fortress at Masyaf in Syria and plundering the surrounding area.

Meanwhile, the diplomatic direction was also pursued, mainly by marrying Ismet, Nur al-Din's widow and also the daughter of the late Damascus ruler Unur. Thus, Saladin easily associated himself with two ruling dynasties at once. There were setbacks along the way, most notably the defeat at Mont Gisard in 1177 to the Franks, also known as western settlers, but victories at Mercu'l-Uyun in 1179 and the capture of a large fortress on the Jordan River helped Saladin gain control of the Middle East. It showed his intention to completely liberate himself from the westerners.

Saladin was also helped by his growing reputation for justice and generosity and his carefully cultivated image as a defender of Islam against rival faiths, especially Christianity. Saladin's position was further strengthened when he captured Aleppo in May 1183 and cautiously built up a very useful Egyptian naval fleet. In 1185, Saladin took control of Mosul and an agreement was signed with the Byzantine Empire against their common adversary, the Seljuks. He could now travel safely to the Latin provinces, knowing that his own borders were secure. While the Franks were distracted by succession disputes and the issue of who would rule the Kingdom of Jerusalem, it was time for Saladin to attack.

In April 1187, the Frankish Fortress of Kerak was attacked, a force commanded by Saladin's son Al-Afdal advanced towards Acre, and Saladin himself led a large army consisting of soldiers from Egypt, Syria, Aleppo and Jazira (northern Iraq). collected. The Franks gathered their forces in response, and the two armies met at Hattin, while the Franks went to Tiberias to relieve Saladin's siege,

Battle of Hattin and Jerusalem

The Battle of Hattin began on July 3, 1187, when Saladin's horse archers repeatedly attacked and retreated, ensuring constant harassment of the marching Franks. As one Muslim historian said: 'the arrows pierced them and turned their lions into hedgehogs' (quoted in Phillips, 162). The next day, a more important clash occurred. Saladin managed to send approximately 20,000 soldiers to Hattin. The Franks were led by Guy of Lusignan, king of the Kingdom of Jerusalem (1186-1192), and could muster approximately 15,000 infantry and 1,300 knights. The Franks were outnumbered and were suffering from a serious water shortage. Meanwhile, the Muslim army, which had plenty of provisions thanks to camel wagons, set fire to dry grass and bushes to further quench the enemy's thirst. The Frankish order broke away from the infantry in disarray and no longer provided the usual protective ring for heavy cavalry. A cavalry force led by Raymond of Tripoli broke through the Muslim lines, but there was no desertion for the rest of the army, and Saladin won a major victory against the largest army the Franks had ever assembled.

In a typically magnanimous move, Saladin offered the now captive Guy an iced sherbet. Some nobles, including Guy, were released for a ransom, as was typical in medieval warfare. Others were less fortunate. Renaud de Châtillon, Prince of Antioch, was hated for his earlier attack on a Muslim caravan and was executed for this. Saladin first swung his scimitar and cut off one of Renaud's arms. Knights of the two military orders, the Knights Templar and the Knights Hospitaller, were deemed too fanatic and too dangerous (plus they had zero chance of obtaining any ransom) and were therefore executed. The rest of the captives were sold into slavery.

In September 1187, Jerusalem, now almost completely undefended, was captured by Saladin, a largely symbolic reward for both sides. Once again, the mass murder of the city's Christians was resisted, and many were either ransomed or made slaves. Eastern Christians were allowed to reside in the city, but all churches except the Holy Sepulcher were converted into mosques.

Other important cities had already come under Saladin's rule, and these included Acre, Tiberias, Caesarea, Nazareth, and Jaffa. In fact, the only important city in the Middle East that was still in western hands was Sur. With the victory at Hattin, the capture of the True Cross, the most sacred relic of the Franks, and the fall of the Holy City of Jerusalem, Saladin's heroic status was confirmed. The Sultan played an active role in promoting his reputation by appointing two official biographers to record his deeds. Likewise, religious and educational institutions were supported, and their works extolled the virtues of their patrons. The Sultan was known for his love of poetry, hunting and gardening. He was also famous for his generosity, especially towards his relatives who governed the provinces of his empire. This generosity and disinterest in accumulating personal wealth is recorded here by modern historian A. Maalouf:

"Treasurers, as revealed by Baha al-Din [Saladin's personal secretary and biographer], always kept a certain sum for emergencies, because they knew that if the lord learned of the existence of this reserve, he would immediately spend it. Despite this precaution, when the sultan died there was one bar of Tyrian gold and forty-seven dirhams of silver in the state treasury. When some of his collaborators scolded him for his extravagance, Saladin replied with a cool smile: "There are people for whom money is not more important than sand."

Third Crusade

Saladin had long entertained the idea of a holy war against the Christian armies of the west, and now that he had captured Jerusalem he would be forced to wage it. Pope III. Gregory (b. 1187) called for a Third Crusade to recapture Jerusalem, and three of Europe's most powerful kings responded: Frederick I Barbarossa (b. 1152-1190), King of Germany and Holy Roman Emperor, King of France II. Philip (b. 1180-1223) and Richard I the Lionheart (b. 1189-1199) of England.

Meanwhile, Guy of Lusignan returned to retrace the expedition. In August 1189 he left Tire with some 7,000 infantry, 400 knights and a small Pisan fleet to begin the siege of Muslim-controlled Acre. It was the beginning of a long and difficult siege, with Saladin's land army laying siege to the Frankish positions, only the final arrival of Philip and Richard's armies tipped the balance in favor of the Crusaders. The city was finally captured on 12 July 1191, and with it the capture of 70 ships, the bulk of Saladin's fleet.

The Crusader army then marched south towards Jerusalem, harassing Saladin's army as it advanced along the coast. Then, on September 7, 1191, a large-scale battle took place in the Arsuf plain. The Crusaders won the day, but Muslim losses were not insignificant – Saladin had no choice but to retreat to the relative safety of the forest surrounding the plain. Although neither Acre nor Arsuf inflicted serious damage on Saladin's army, two consecutive defeats and the subsequent loss of Jaffa to Richard I in August 1192 collectively damaged Saladin's military reputation among his contemporaries.

Criticism of Saladin's Strategy

Saladin was often criticized by rival Muslim leaders for being too careful when direct attacks on Tire could have prevented the Crusaders from becoming a crucial beachhead, and similarly for not engaging Guy's army before it reached Acre or the besieged Crusader army. All these hamlets could have been used. However, this was criticism with the benefit of hindsight and ignores the rules of warfare widely established throughout the region at the time. An army of any kind very rarely engages in open warfare directly with the enemy. Control of strategically important fortresses and ports through siege warfare was the standard exercise of the day. In the absence of determination to take Tire, the last Frankish stronghold, Saladin, wary of the arrival of Frederick I's massive army (which never arrived at the time of the incident), opted to retain faith in the tried and tested method of wearing down the enemy at their weakest points rather than their strongest. It is more difficult to defend Selahaddin, except for his actions. He also saw that the kings of the West could not stay in the East forever and therefore neglect their own kingdoms; Time was always on the side of Muslims. And as it turned out, Saladin's approach was successful, as the Crusader army was greatly exhausted by the time it reached Jerusalem, its primary objective, and Saladin's army was still such a threat that the entire Crusade was disbanded in the fall. A negotiation followed, but Richard gained little for all the effort expended on his cause, unable even to meet his opponent face to face. Meanwhile, Saladin held Jerusalem, the strong tide of the Third Crusade had passed, and his empire was intact.

Death and Legacy

Saladin did not benefit from the departure of the Crusaders because he died shortly afterwards in Damascus on March 4, 1193. He was only 55 or 56 years old and likely died from the physical toll of the decades spent on the campaign. The fragile and often volatile Muslim coalition quickly disintegrated after its major leaders died, with three of Saladin's sons seizing control of Egypt, Damascus, and Aleppo respectively, while other relatives and emirs squabbled over the rest. Saladin left a lasting legacy by establishing the Ayyubid dynasty, which reigned in Egypt until 1250 and in Syria until 1260, before being overthrown in both cases by the Mamluks. Saladin also left a legacy in both Muslim and Christian literature. Indeed, it is somewhat ironic that the Muslim leader became one of the greatest examples of chivalry in 13th-century European literature. Much has been written about the sultan during and after his lifetime, but the fact that an appreciation for his diplomacy and leadership skills can be found in both contemporary Muslim and Christian sources shows that Saladin was indeed worthy of his place as a great medieval leader.

If you want to see more such historical figures, don't forget to follow and comment.