If Kafka Wrote About Crypto: Bureaucracy on the Blockchain

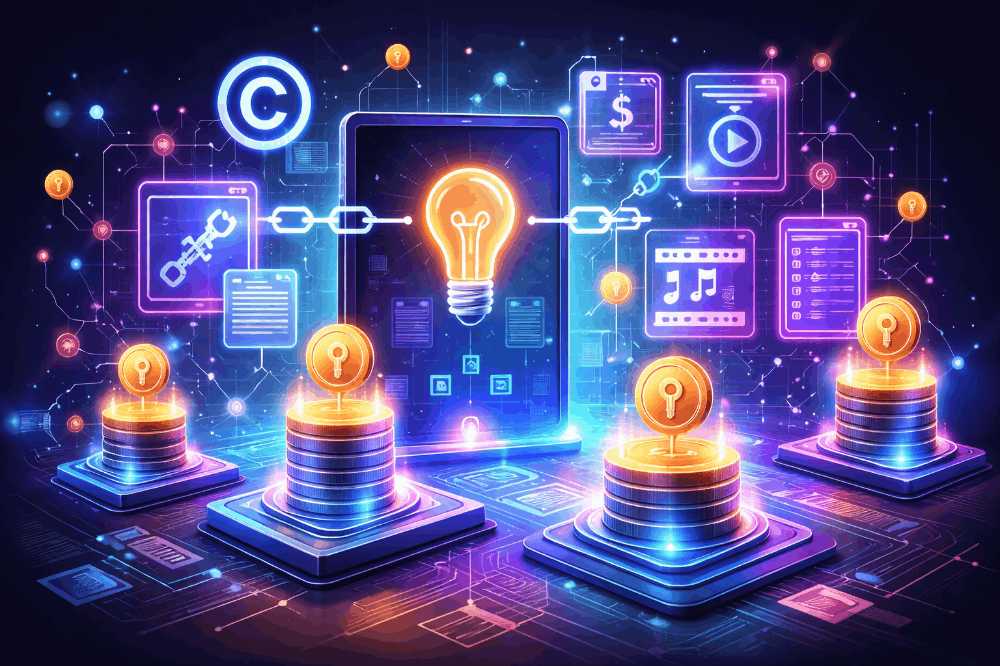

Franz Kafka’s work captured the absurdity of systems labyrinthine bureaucracies, faceless authority, and processes that seem to exist solely to perpetuate themselves. Now imagine if Kafka had access to Ethereum. It may sound like a contradiction: after all, blockchains are supposed to simplify and decentralize, not complicate.

But a closer inspection of how blockchain ecosystems operate reveals that the ghosts of Kafka’s world have not disappeared. They've simply migrated into new codebases, protocols, and governance models.

The Bureaucratic Machinery Behind Decentralization

The promise of decentralization was freedom from centralized choke points. No more single points of failure, no arbitrary gatekeepers, and no top-down control. But this ideal often clashes with the practicalities of coordinating decentralized actors.

Take DAOs (Decentralized Autonomous Organizations), for instance. Billed as a new form of organizational governance, DAOs are designed to automate decision-making through smart contracts and community voting. But the user experience is frequently opaque. Endless proposal threads, convoluted voting procedures, and dependency on token-weighted consensus all introduce a new flavor of bureaucracy one enforced not by a clerk behind a desk, but by lines of immutable code.

Participation in these systems often requires navigating dense documentation, understanding niche terminology, and adhering to rigid process flows. In other words, to be a member of many DAOs today is to endure a digital version of Kafka’s The Castle—eternally attempting to gain entry, only to discover the rules are arbitrary, shifting, and authored by no one in particular.

Smart Contracts as the New Bureaucrats

Kafka’s characters often find themselves trapped in systems they cannot understand or control. In blockchain, the analog might be the smart contract. Once deployed, these self-executing agreements are immutable by design. They operate exactly as written, regardless of intent or context.

This leads to situations where a poorly written function can lock away millions in funds, or where a contract's logic inadvertently favors one group over another. There is no appeal, no administrator to contact, no human judge to override the system. Like Kafka’s The Trial, where the protagonist is arrested without ever being told the charges, interacting with some blockchain protocols can feel like engaging with a system that refuses to explain itself.

Smart contracts promise transparency, but only to those literate in code. To everyone else, they are black boxes, immutable and merciless. Code becomes law, and law becomes estranged from justice.

The Irony of Permissionless Systems

Blockchain systems are often described as "permissionless"—anyone can participate, no need for prior approval. But while that’s true on a technical level, social and financial layers introduce hidden gatekeeping.

For example, participation in a DAO’s governance may require holding a certain number of tokens. Access to early-stage projects often depends on insider knowledge or connections. Navigating a new protocol often demands hours of unpaid labor reading whitepapers, watching tutorials, participating in forums. While the blockchain may not check your passport or verify your identity, it does quietly demand that you possess time, technical knowledge, and capital.

This is not far from Kafka’s nightmarish depiction of systems where entrance appears open to all but is in practice only accessible to a select few. In Before the Law, a man spends his entire life waiting for access to a gate that was "meant only for him," but he is never allowed in. Similarly, Web3 promises open access, but the invisible costs of participation can be prohibitively high.

Governance Theatre: The Appearance of Control

Token-based voting is often held up as a solution to centralized control. But in practice, it can mimic the same power imbalances it seeks to eliminate. Wealthy token holders dominate outcomes, and many votes pass with low participation rates. Quorum thresholds may not be met, and important proposals are sometimes decided by a tiny fraction of the community.

This creates a kind of “governance theatre” the appearance of democratic process without its substance. The mechanisms are there, and anyone can participate, but the outcomes are often predetermined by capital concentration or apathy. It's not unlike Kafka's The Trial, where the protagonist is encouraged to make his case despite knowing that the verdict has already been decided.

Moreover, the effort required to stay informed in a DAO can be exhausting. Constant governance proposals, economic modeling, code audits, and community discussions demand a level of attention that few can consistently provide. As a result, decision-making often defaults to insiders, developers, or whales those with the time and resources to wade through the minutiae.

Immutability and the Tyranny of the Unchangeable

In Kafka's world, nothing ever really changes. The system perpetuates itself, and the characters are trapped in cycles of repetition. Blockchain’s commitment to immutability creates a similar dynamic. Once a contract is deployed, once a token economy is launched, rolling back becomes almost impossible.

Even when a problem is recognized, the path to fixing it is fraught with difficulty. Forking a project, proposing contract upgrades, or amending governance structures all involve considerable overhead, often requiring community consensus that is difficult to achieve.

This rigidity can result in technical debt and social stagnation. Protocols may carry forward flawed incentives, broken designs, or inefficient code simply because changing them is too complicated or too contentious. The blockchain becomes a mausoleum of early decisions—decisions that live on not because they’re right, but because they’re irreversible.

The Human Element: Lost in Translation

Perhaps the most Kafkaesque quality of blockchain ecosystems is their disconnection from human experience. Transactions are reduced to hashes, users are wallet addresses, and actions are validated by code, not context. There's little room for empathy, discretion, or nuance.

In Kafka’s stories, individuals are reduced to cogs in an unfeeling machine. Similarly, in blockchain, trustlessness is prized over trust, anonymity over identity, automation over conversation. These choices serve important functions especially in hostile or untrustworthy environments but they also create distance. In doing so, they replicate the very alienation that Kafka so poignantly described.

Conclusion

Blockchain was born out of a desire to escape centralized control, to build systems that are more just, transparent, and inclusive. And yet, without careful attention, these same systems risk becoming new arenas for the old pathologies: opacity, exclusion, rigidity, and alienation.

If Kafka were writing today, he might not be surprised to find that even in a world of cryptographic proofs and smart contracts, bureaucracy survives. It simply changes form. He would likely remind us that the fight for decentralization is not only about technology but also about values how systems treat people, not just how they function.

The challenge for crypto builders is not merely to avoid centralization but to resist the emergence of a new digital bureaucracy one that hides behind technical abstraction, alienates its users, and confuses structure for progress. Kafka’s legacy warns us of what happens when systems serve themselves instead of the people inside them.

If blockchain is to be more than a Kafkaesque labyrinth, it must make room for the human.