Reflective Notes #01 Loving Fate in Times of Anesthesia

Reflective Notes #01

Loving Fate in Times of Anesthesia

The city of Troy is under siege. Outside its walls, the Greek army organizes itself like a war machine, among them, the fearsome Achilles waits. Inside the city, Hector prepares for combat. The corridors echo fear, parents sense the coming loss, the people fall silent, Andromache foresees mourning. Amid these ominous signs, Hector addresses his wife, affirming his position before fate, refusing both flight and the illusion of safety:

“No man, I tell you, will send me to Hades against my fate;

no one has ever escaped his portion,

coward or brave, from the moment he is born.”

(Iliad, Book VI)

At first glance, the speech may sound like the bravado of a man caught in the fury of war. Yet its deeper meaning reveals tragic lucidity. Hector does not walk toward death out of ignorance, nor does he deny it. He remains steadfast in what he can do and, above all, affirms that over which his will is powerless. If the hour of death has come, it will be affirmed with the same cry as life itself. The sentence is not an external punishment, but the very form of the world fulfilling itself through the body of the hero.

This scene precisely illustrates the position of Greek heroes before the tragic: the full affirmation of the inevitability of fate. It is a recurring stance in Greek tragedy, the story of Oedipus is well known, realizing his destiny precisely by trying to escape it.

At this point, an ethical stance emerges that seems largely forgotten in contemporary society. In Nietzsche and Philosophy, Gilles Deleuze develops central observations on Nietzsche’s reading of tragedy. For Nietzsche, tragedy is neither a pedagogy of guilt nor a lesson in resignation, but an affirmative gesture. It teaches how to say Yes. Not to this or that isolated circumstance, but to the totality of life, with all that it carries in excess, pain, and contradiction.

This tragic Yes is the key to understanding amor fati. Hector’s response is permeated by this Yes: without fear of what is to come, without desiring death, yet without refusing it. Hector loves fate not as something he wants, but as an inevitable fatality, traced by forces far greater than his human limitation. Faced with this, at once honor and burden, no other ethical possibility remains than to love the fate the gods have reserved for him.

There is a fundamental difference between accepting what happens and loving what happens. The former may arise from exhaustion, adaptation, or impotence. The latter requires a radical conversion of perspective. Amor fati, loving one’s fate, is not elegant resignation, but one of the most demanding proposals ever formulated by philosophy. Made famous by Friedrich Nietzsche, the expression carries a tension that runs through the entire philosophical tradition: how can life be affirmed without resorting to transcendence, future compensation, or promises of external meaning?

In the tradition of Antiquity, fate appears as inexorable, something imposed upon the subject. For the Stoics, such as Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius, wisdom consisted in aligning individual will with the order of the world: not wishing for things to happen as we want them to, but wanting them to happen as they do happen. There was in this a powerful ethic, capable of freeing the subject from useless suffering, born of resistance to the inevitable. Even so, the idea of a rational order of the world remained, to which one should adjust.

Amor fati, in its tragic formulation, radically displaces this position. In analyzing the origins of tragedy, Nietzsche detaches love of fate from any reconciliation with a rational order. The submissive position is abandoned in favor of an affirmative role. This is an ethical maneuver at once subtle and complex: being willing to love life without guarantees, without the support of prior meanings, without aiming at an ultimate purpose as justification for present actions.

It is a matter of intensifying life, assuming that both what makes us happy and the challenges we face are inherent to living. One must love the fate that falls to us, saying yes not only to what is pleasant, but also, and above all, to what wounds, fails, and interrupts. Not because suffering is good in itself, but because it is inseparable from the very experience of living. Here, amor fati distances itself from any morality of compensation. What remains is the question, tied to eternal recurrence: would you accept living this same life, exactly as it is, eternally?

Using the cosmological question as an ethical criterion of affirmation, are we willing to affirm every minimal detail of our present life? As a practical exercise, this means affirming not only complex decisions, but also the trivialities of everyday life. Beyond the valuation of small and great acts, the possibility of loving fatality and affirming life in its totality is the true proof of freedom.

We usually oppose fate and freedom as incompatible terms: either we are free, or we are determined. Amor fati dissolves this opposition. Freedom does not lie in choosing events, but in choosing one’s relation to them. I do not choose what happens to me, but I choose how I position myself toward it. This is a psychological gesture that derives from an ontological affirmation: transforming what happens into a constitutive part of who one is.

The subject who loves their fate is not passive; they incorporate into life the very act of living. They make chance a constitutive matter of themselves.

However, it is necessary to consider the contemporary context: the way information circulates and, above all, how it is consumed. Faced with the market driven desire for tools that promise to save life from everyday suffering, amor fati risks being converted into a therapeutic slogan, a simulacrum of potency that merely adapts the subject to a reality that remains untouched.

Nietzsche warned against those who trade life for comfort, refusing the wagon of beautiful possibilities in the name of security. The affirmative gesture is only possible when one breaks with reactive logic. Loving fate requires abandoning the position of victim, but also that of innocence. It requires recognizing that what happens to us, including what we do not choose, enters into the account of who we become.

This stance is ethical in the precise sense that Gilles Deleuze attributes to ethics when reading Nietzsche and Spinoza. It is not a matter of judging the world through transcendent values, nor of absolving or condemning events, but of evaluating modes of existence. This is exactly the gesture manifested in Hector’s response before the walls of Troy: he does not ask fate for justice, does not negotiate meaning, does not await redemption, he simply affirms the place that belongs to him in the course of events.

For this reason, this position does not justify injustices, does not romanticize pain, nor absolve structures of exploitation or inequality. It merely refuses the deeply moral idea that life must be corrected in order to be worth living. In a world marked by material instability, precariousness, and social inequality, amor fati offers no easy consolation and promises no individual exits from collective problems. It teaches how to leave the logic of adaptation and enter the terrain of active choices, creating a way of remaining whole in the face of uncertainty and instability.

At this point, the proximity to Baruch Spinoza becomes decisive. For Spinoza, ethics does not correct reality, nor does it moralize it. It seeks to understand how bodies and affects compose themselves, increasing or decreasing their power to exist. Affirmation is not approval, but lucidity.

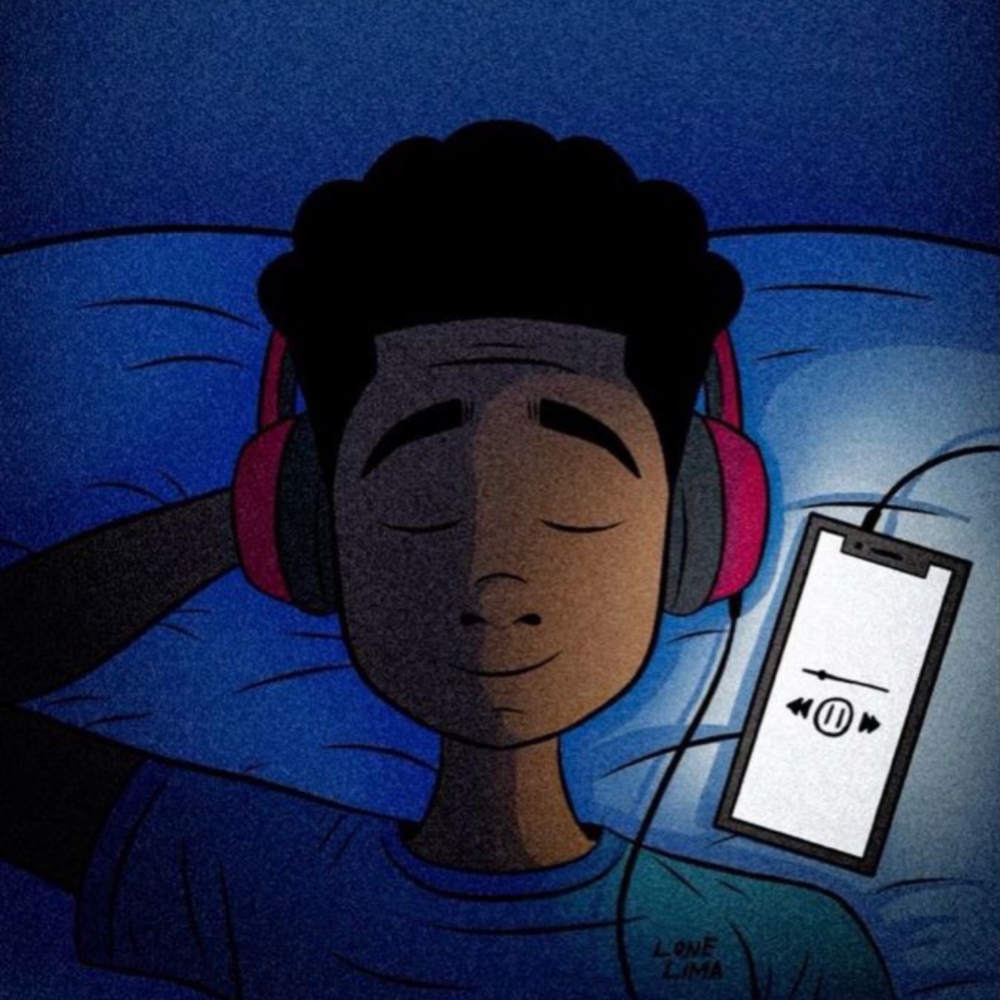

In a world where afflictions are broadcast live, we are progressively anesthetized by the glow of screens. Pain circulates, but does not pass through us, catastrophe repeats itself until it loses density. When the logic of productivity becomes organic, when even suffering must yield performance, philosophy comes to be treated as superfluous. Yet it is precisely an ethical position, and not a morality of adaptation, that makes any transformation possible. There is no collective change without an individual stance that refuses the comfortable passivity of bubbles and the continuous delegation of fate.

It is at this point that the ethics of amor fati reappears in its most radical possibility: not as consolation, but as anchoring.

Perhaps this is what tragic thought still has to tell us: to recover protagonism over one’s own way of existing in a world that constantly pushes us toward anesthesia, automatic reaction, and the outsourcing of destiny. Loving fate, here, is not closing one’s eyes to the violence of the real, nor confusing acceptance with resignation. It is inhabiting the world with wholeness, affirming one’s presence within the flow of what happens, even when everything conspires to reduce us to the condition of spectators. It is to make existence itself an affirmative gesture.