Mark Zuckerberg

Part of Zuckerberg’s problem-solving methodology appears to be to start from the position that all problems are solvable, and moreover solvable by him. As a first step, he crunched some numbers. They were big numbers, but he’s comfortable with those: if he does nothing else, Zuckerberg scales. The population of the earth is currently about 7.2 billion. There are about 2.9 billion people on the Internet, give or take a hundred million. That leaves roughly 4.3 billion people who are offline and need to be put online. “What we figured out was that in order to get everyone in the world to have basic access to the Internet, that’s a problem that’s probably billions of dollars,” he says. “Or maybe low tens of billions. With the right innovation, that’s actually within the range of affordability.”

Zuckerberg made some calls, and the result was the formation last year of a coalition of technology companies that includes Ericsson, Qualcomm, Nokia and Samsung. The name of this group is Internet.org, and it describes itself as “a global partnership between technology leaders, nonprofits, local communities and experts who are working together to bring the Internet to the two-thirds of the world’s population that doesn’t have it.”

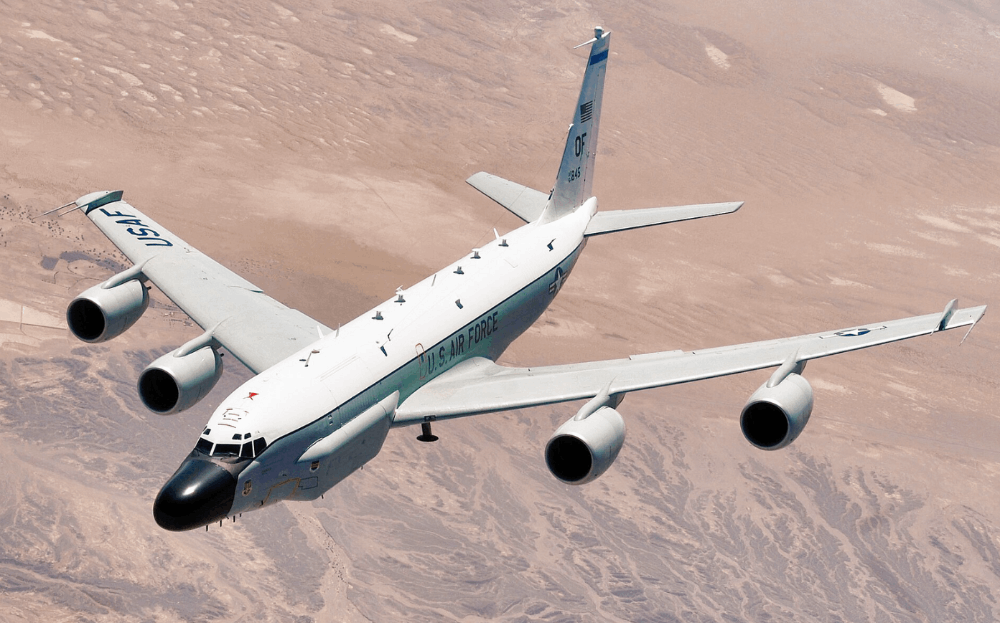

Based on that, you might think that -Internet.org will be setting up free wi-fi in the Sahara and things like that, but as it turns out, the insight that makes the whole thing feasible is that it’s not about building new infrastructure. Using maps and data from Ericsson and NASA—-including a fascinating data set called the Gridded Population of the World, which maps the geographical distribution of the human species—plus information mined from Facebook’s colossal user base, the -Internet.org team at Facebook figured out that most of their work was already done. Most humans, or about 85% of them, already have Internet access, at least in the minimal sense that they live within range of a cell tower with at least a 2G data network. They’re just not using it.

Facebook has a plan for the other 15%, a blue-sky wi-fi-in-the-Sahara-type scheme involving drones and satellites and lasers, which we’ll get to later, but that’s a long-term project. The subset of that 85% of people who could be online but aren’t: they’re the low-hanging fruit.

But why aren’t they online already? To not be on the Internet when you could be: from the vantage point of Silicon Valley, that is an alien state of being. The issues aren’t just technical; they’re also social and economic and cultural. Maybe these are people who don’t have the money for a phone and data plan. Maybe they don’t know enough about the Internet. Or maybe they do know enough about it and just don’t care, because it’s totally irrelevant to their day-to-day lives.

(Interactive: How Much Time Have You Wasted on Facebook?)

You’d think Zuckerberg the arch-hacker wouldn’t sully his hands with this kind of soft-science stuff, but in fact he doesn’t blink at it. He attacks social/economic/cultural problems the same way he attacks technical ones; in fact it’s not clear that he makes much of a distinction between them. Human nature is just more code to hack—never forget that before he dropped out, Zuckerberg was a psych major. “If you grew up and you never had a computer,” he says, “and you’ve never had access to the Internet, and somebody asked you if you wanted a data plan, your answer would probably be, ‘What’s a data plan?’ Right? Or, ‘Why would I want that?’ So the problems are different from what people think, but they actually end up being very tractable.”

Zuckerberg is a great one for breaking down messy, wonky problems into manageable chunks, and when you break this one down it falls into three buckets. Business: making the data cheap enough that people in developing countries can pay for it. Technology: simplifying the content and/or services on offer so that they work in ultra-low-bandwidth situations and on a gallimaufry of old, low-end hardware. And content: coming up with content and/or services compelling enough to somebody in the third world that they would go through the trouble of going online to get them. Basically the challenge is to imagine what it would be like to be a poor person—the kind of person who lives somewhere like Chandauli.

Engineering Empathy

The Facebook campus in Menlo Park, Calif., isn’t especially conducive to this. It’s about as far from Chandauli, geographically, aesthetically and socioeconomically, as you can get on this planet. When you walk into Facebook’s headquarters for the first time, the overwhelming impression you get is of raw, unbridled plenitude. There are bowls overflowing with free candy and fridges crammed with free Diet Coke and bins full of free Kind bars. They don’t have horns with fruits and vegetables spilling out of them, but they might as well.

The campus is built around a sun-drenched courtyard crisscrossed by well-groomed employees strolling and laughing and wheeling bikes. Those Facebookies who aren’t strolling and laughing and wheeling are bent over desks in open-plan office areas, looking ungodly busy with some exciting, impossibly hard task that they’re probably being paid a ton of money to perform. Arranged around the courtyard (where the word hack appears in giant letters, clearly readable on Google Earth if not from actual outer space) are -restaurants—Lightning Bolt’s Smoke Shack, Teddy’s Nacho Royale, Big Tony’s Pizzeria—that seem like normal restaurants right up until you try to pay, when you realize they don’t accept money. Neither does the barbershop or the dry cleaner or the ice cream shop. It’s all free.

You’re not even in the first world anymore, you’re beyond that. This is like the zeroth world. And it’s just the shadow of things to come: a brand-new campus, designed by Frank Gehry, natch, is under construction across the expressway. It’s slated to open next year.

(Because of the limits of space and time, a lot of Silicon Valley companies don’t build new headquarters; they just take over the discarded offices of older firms, like hermit crabs. Facebook’s headquarters used to belong to Sun Microsystems, a onetime power-house of innovation that collapsed and was acquired by Oracle in 2009. When Facebook moved in, Zuckerberg made over the whole place, but he didn’t change the sign out front, he just turned it around and put Facebook on the other side. The old sign remains as a reminder of what happens when you take your eye off the ball.)

As Zuckerberg himself puts it, when you work at a place like Facebook, “it’s easy to not have empathy for what the experience is for the majority of people in the world.” To avoid any possible empathy shortfall, Facebook is engineering empathy artificially. “We re-created with the Ericsson network guys the network conditions that you have in rural India,” says Javier Olivan, Facebook’s head of growth. “Then we brought in some phones, like very low-end Android, and we invited guys from the Valley here—the eBay guys, the Apple guys. It’s like, Hey, come and test your applications in these conditions! Nothing worked.” It was a revelation: for most of humanity, the Internet is broken. “I force a lot of the guys to use low-end phones now,” Olivan says. “You need to feel the pain.”

sandbergTo facilitate the pain-feeling, Facebook is building an entire permanent lab dedicated to the study of suboptimal computing conditions. “You actually retool the company to start to measure, What does the experience look like for the majority of the world?” says Chris Daniels, who heads Facebook’s -Internet.org team. Developers began testing apps not just on the current version of Android but on all Androids ever: 2012, 2011, 2010 and so on. They maintain a carefully curated collection of crappy old flip phones. They even modified their vocabulary. “A lot of times people call it low-end—this is a low-end Android phone, or this is a low-end network,” Zuckerberg says. “But it’s actually not. It’s a typical Android phone and a typical network. So internally we are not allowed to call it low-end. You have to refer to it as typical.”

Needless to say, in all the time I spent at Facebook, I never heard anybody call it that. They just called it low-end. But his point stands.

Internet 911

Not to keep you in suspense, but Facebook figured out the answer to how to get all of humanity online. It’s an app.

Here’s the idea. First, you look at a particular geographical region that’s underserved, Internet-wise, and figure out what content might be compelling enough to lure its inhabitants online. Then you gather that content up, make sure it’s in the right language and wrap it up in a slick app. Then you go to the local cell-phone providers and convince as many of them as possible that they should offer the content in your app for free, with no data charges. There you go: anybody who has a data-capable phone has Internet access—or at least access to a curated, walled sliver of the Internet—for free.

This isn’t hypothetical: Internet.org released this app in Zambia in July. It launched in Tanzania in October. In Zambia, the app’s content offerings include AccuWeather, Wikipedia, Google Search, the Mobile Alliance for Maternal Action—there’s a special emphasis on women’s rights and women’s health—and a few job-listing sites. And Facebook. A company called Airtel (the local subsidiary of an Indian telco) agreed to offer access for nothing. “I think about it like 911 in the U.S.,” Zuckerberg says. “You don’t have to have a phone plan, but if there’s an emergency, if there’s a fire or you’re getting robbed, you can always call and get access to those kinds of basic services. And I kind of think there should be that for the Internet too.”

This makes it sound simpler than it is. For Facebook to simply reach out from Silicon Valley and blanket a country like Zambia with content requires exactly the kind of nuance and sensitivity that Facebook is not famous for. Just figuring out what language the content should be in is a challenge. The official language in Zambia is English, but the CIA’s World Factbook lists 17 languages spoken there. And Zambia is cake compared with India, which has no national language but officially recognizes 22 of them; unofficially, according to a 2011 census, India’s 1.2 billion inhabitants speak a total of 1,635 languages. It is, in the words of one Facebook executive, “brutally localized.”

But the hardest part is persuading the cell-phone companies to offer the content for free. The idea is that they should make the app available as a loss leader, and once customers see it (inside Facebook they talk about people being “exposed to data”), they’ll want more and be willing to pay for it. In other words, data is addictive, so you make the first taste free.

This part is crucial. It’s not enough for the app to work—the scheme has to replicate itself virally, driven by cell-phone companies acting in their own self-interest. It’s a business hack as much as it is a technical one. Before Zambia, Facebook tried a limited run in the Philippines with a service provider called Globe, which reported nearly doubling its registered mobile data-service users over three months. There’s your proof of concept.

The more test cases Facebook can show off, the easier it will be to persuade telcos to sign on. The more telcos that sign on, the more data Facebook compiles and the stronger its case gets. Eventually the model begins to spread by itself, region by region, country by country, and as it replicates it draws more and more people online. “Each time we do the integration, we tune different things with the operator and it gets better and better and better,” Zuckerberg says. “The thing that we haven’t proven definitely yet is that it’s valuable for them to offer those basic services for free indefinitely, rather than just as a trial. Once we have that, we feel like we’ll be ready to go around to all the other operators in the world and say, This is definitely a good model for you. You should do this.” (There’s a quiet arrogance to it, as there is to a lot of what Facebook does. Facebook is basically saying, Hey, third-world cell-phone operators, by the way, your business model? Let us optimize it for you.)