Albert Einstein (1)

Albert Einstein

"Einstein" redirects here. For other uses, see Einstein (disambiguation) and Albert Einstein (disambiguation).

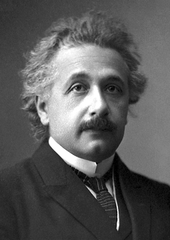

Albert Einstein Portrait by Ferdinand Schmutzer, 1921

Portrait by Ferdinand Schmutzer, 1921

Born14 March 1879

Ulm, Kingdom of Württemberg, German EmpireDied18 April 1955 (aged 76)

- Princeton, New Jersey, U.S.CitizenshipKingdom of Württemberg, part of the German Empire (until 1896)[note 1]

- Stateless (1896–1901)

- Switzerland (1901–1955)

- Austria, part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire (1911–1912)

- Kingdom of Prussia, part of the German Empire (1914–1918)[note 1]

- Free State of Prussia (Weimar Republic, 1918–1933)[note 1]

- United States (1940–1955)

EducationFederal polytechnic school (Dipl., 1900)

- University of Zurich (PhD, 1905)Known forGeneral relativity

- Special relativity

- Photoelectric effect

- E=mc2 (mass–energy equivalence)

- E=hf (Planck–Einstein relation)

- Theory of Brownian motion

- Einstein field equations

- Bose–Einstein statistics

- Bose–Einstein condensate

- Gravitational wave

- Cosmological constant

- Unified field theory

- EPR paradox

- Ensemble interpretation

- List of other concepts

- Spouses

Mileva Marić

(m. 1903; div. 1919)

Elsa Löwenthal

(m. 1919; died 1936)

- ChildrenLieserlHans AlbertEduard "Tete"

- AwardsBarnard Medal (1920)

- Nobel Prize in Physics (1921)

- Matteucci Medal (1921)

- ForMemRS (1921)[1]

- Copley Medal (1925)[1]

- Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society (1926)[2]

- Max Planck Medal (1929)

- Member of the National Academy of Sciences (1942)[3]

- Time Person of the Century (1999)

- Scientific careerFieldsPhysics, philosophyInstitutionsSwiss Patent Office (Bern) (1902–1909)

- University of Bern (1908–1909)

- University of Zurich (1909–1911)

- Charles University in Prague (1911–1912)

- ETH Zurich (1912–1914)

- Prussian Academy of Sciences (1914–1933)

- Humboldt University of Berlin (1914–1933)

- Kaiser Wilhelm Institute (director, 1917–1933)

- German Physical Society (president, 1916–1918)

- Leiden University (visits, 1920)

- Institute for Advanced Study (1933–1955)

- California Institute of Technology (visits, 1931–1933)

- University of Oxford (visits, 1931–1933)

- Brandeis University (director, 1946–1947)

ThesisEine neue Bestimmung der Moleküldimensionen (A New Determination of Molecular Dimensions) (1905)Doctoral advisorAlfred KleinerOther academic advisorsHeinrich Friedrich WeberSignature Albert Einstein (/ˈaɪnstaɪn/ EYEN-styne;[4] German: [ˈalbɛɐt ˈʔaɪnʃtaɪn] ⓘ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist who is widely held to be one of the greatest and most influential scientists of all time. Best known for developing the theory of relativity, Einstein also made important contributions to quantum mechanics, and was thus a central figure in the revolutionary reshaping of the scientific understanding of nature that modern physics accomplished in the first decades of the twentieth century.[1][5] His mass–energy equivalence formula E = mc2, which arises from relativity theory, has been called "the world's most famous equation".[6] He received the 1921 Nobel Prize in Physics "for his services to theoretical physics, and especially for his discovery of the law of the photoelectric effect",[7] a pivotal step in the development of quantum theory. His work is also known for its influence on the philosophy of science.[8][9] In a 1999 poll of 130 leading physicists worldwide by the British journal Physics World, Einstein was ranked the greatest physicist of all time.[10] His intellectual achievements and originality have made the word Einstein broadly synonymous with genius.[11]

Albert Einstein (/ˈaɪnstaɪn/ EYEN-styne;[4] German: [ˈalbɛɐt ˈʔaɪnʃtaɪn] ⓘ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist who is widely held to be one of the greatest and most influential scientists of all time. Best known for developing the theory of relativity, Einstein also made important contributions to quantum mechanics, and was thus a central figure in the revolutionary reshaping of the scientific understanding of nature that modern physics accomplished in the first decades of the twentieth century.[1][5] His mass–energy equivalence formula E = mc2, which arises from relativity theory, has been called "the world's most famous equation".[6] He received the 1921 Nobel Prize in Physics "for his services to theoretical physics, and especially for his discovery of the law of the photoelectric effect",[7] a pivotal step in the development of quantum theory. His work is also known for its influence on the philosophy of science.[8][9] In a 1999 poll of 130 leading physicists worldwide by the British journal Physics World, Einstein was ranked the greatest physicist of all time.[10] His intellectual achievements and originality have made the word Einstein broadly synonymous with genius.[11]

Born in the German Empire, Einstein moved to Switzerland in 1895, forsaking his German citizenship (as a subject of the Kingdom of Württemberg)[note 1] the following year. In 1897, at the age of seventeen, he enrolled in the mathematics and physics teaching diploma program at the Swiss Federal polytechnic school in Zürich, graduating in 1900. In 1901, he acquired Swiss citizenship, which he kept for the rest of his life. In 1903, he secured a permanent position at the Swiss Patent Office in Bern. In 1905, he submitted a successful PhD dissertation to the University of Zurich. In 1914, he moved to Berlin in order to join the Prussian Academy of Sciences and the Humboldt University of Berlin. In 1917, he became director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics; he also became a German citizen again, this time as a subject of the Kingdom of Prussia.[note 1] In 1933, while he was visiting the United States, Adolf Hitler came to power in Germany. Horrified by the Nazi "war of extermination" against his fellow Jews,[12] Einstein decided to remain in the US, and was granted American citizenship in 1940.[13] On the eve of World War II, he endorsed a letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt alerting him to the potential German nuclear weapons program and recommending that the US begin similar research. Einstein supported the Allies but generally viewed the idea of nuclear weapons with great dismay.[14]

In 1905, a year sometimes described as his annus mirabilis (miracle year), Einstein published four groundbreaking papers.[15] These outlined a theory of the photoelectric effect, explained Brownian motion, introduced his special theory of relativity—a theory which addressed the inability of classical mechanics to account satisfactorily for the behavior of the electromagnetic field—and demonstrated that if the special theory is correct, mass and energy are equivalent to each other. In 1915, he proposed a general theory of relativity that extended his system of mechanics to incorporate gravitation. A cosmological paper that he published the following year laid out the implications of general relativity for the modeling of the structure and evolution of the universe as a whole.[16][17] The middle part of his career also saw him making important contributions to statistical mechanics and quantum theory. Especially notable was his work on the quantum physics of radiation, in which light consists of particles, subsequently called photons.

For much of the last phase of his academic life, Einstein worked on two endeavors that proved ultimately unsuccessful. Firstly, he advocated against quantum theory's introduction of fundamental randomness into science's picture of the world, objecting that "God does not play dice".[18] Secondly, he attempted to devise a unified field theory by generalizing his geometric theory of gravitation to include electromagnetism too. As a result, he became increasingly isolated from the mainstream of modern physics.

Life and career

Childhood, youth and education

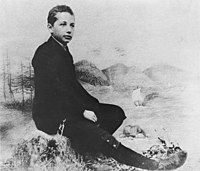

See also: Einstein family Einstein in 1882, age 3

Einstein in 1882, age 3

Albert Einstein was born in Ulm,[19] in the Kingdom of Württemberg in the German Empire, on 14 March 1879.[20][21] His parents, secular Ashkenazi Jews, were Hermann Einstein, a salesman and engineer, and Pauline Koch. In 1880, the family moved to Munich's borough of Ludwigsvorstadt-Isarvorstadt, where Einstein's father and his uncle Jakob founded Elektrotechnische Fabrik J. Einstein & Cie, a company that manufactured electrical equipment based on direct current.[19]

Albert attended a Catholic elementary school in Munich from the age of five. When he was eight, he was transferred to the Luitpold-Gymnasium (now known as the Albert-Einstein-Gymnasium [de]) where he received advanced primary and then secondary school education.[22]

In 1894, Hermann and Jakob's company tendered for a contract to install electric lighting in Munich, but without success—they lacked the capital that would have been required to update their technology from direct current to the more efficient, alternating current alternative.[23] The failure of their bid forced them to sell their Munich factory and search for new opportunities elsewhere. The Einstein family moved to Italy, first to Milan and a few months later to Pavia, where they settled in Palazzo Cornazzani.[24] Einstein, then fifteen, stayed behind in Munich in order to finish his schooling. His father wanted him to study electrical engineering, but he was a fractious pupil who found the Gymnasium's regimen and teaching methods far from congenial. He later wrote that the school's policy of strict rote learning was harmful to creativity. At the end of December 1894, a letter from a doctor persuaded the Luitpold's authorities to release him from its care, and he joined his family in Pavia.[25] While in Italy as a teenager, he wrote an essay entitled "On the Investigation of the State of the Ether in a Magnetic Field".[26][27]

Einstein excelled at physics and mathematics from an early age, and soon acquired the mathematical expertise normally only found in a child several years his senior. He began teaching himself algebra, calculus and Euclidean geometry when he was twelve; he made such rapid progress that he discovered an original proof of the Pythagorean theorem before his thirteenth birthday.[28][29][30] A family tutor, Max Talmud, said that only a short time after he had given the twelve year old Einstein a geometry textbook, the boy "had worked through the whole book. He thereupon devoted himself to higher mathematics ... Soon the flight of his mathematical genius was so high I could not follow."[31] Einstein recorded that he had "mastered integral and differential calculus" while still just fourteen.[29] His love of algebra and geometry was so great that at twelve, he was already confident that nature could be understood as a "mathematical structure".[31]

- Einstein in 1893, age 14Part of a series onPhysical cosmologyBig Bang · Universe

- Age of the universe

- Chronology of the universe

show

Early universe

show

Expansion · Future

show

Components · Structure

show

hide

Scientists

- AaronsonAlfvénAlpherBharadwajCopernicusde SitterDickeEhlersEinsteinEllisFriedmannGalileoGamowGuthHawkingHubbleKeplerLemaîtreMatherNewtonPenrosePenziasRubinSchmidtSmootSuntzeffSunyaevTolmanWilsonZeldovich

- List of cosmologists

show

vte

At thirteen, when his range of enthusiasms had broadened to include music and philosophy,[32] Einstein was introduced to Kant's Critique of Pure Reason. Kant became his favorite philosopher; according to his tutor, "At the time he was still a child, only thirteen years old, yet Kant's works, incomprehensible to ordinary mortals, seemed to be clear to him."[31] Einstein's Matura certificate, 1896[note 2]

Einstein's Matura certificate, 1896[note 2]

In 1895, at the age of sixteen, Einstein sat the entrance examination for the Federal polytechnic school (later the Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule, ETH) in Zürich, Switzerland. He failed to reach the required standard in the general part of the test,[33] but performed with distinction in physics and mathematics.[34] On the advice of the polytechnic's principal, he completed his secondary education at the Argovian cantonal school (a gymnasium) in Aarau, Switzerland, graduating in 1896. While lodging in Aarau with the family of Jost Winteler, he fell in love with Winteler's daughter, Marie. (His sister, Maja, later married Winteler's son Paul.[35])

In January 1896, with his father's approval, Einstein renounced his citizenship of the German Kingdom of Württemberg in order to avoid conscription into military service.[36] The Matura (graduation for the successful completion of higher secondary schooling) awarded to him in the September of that year acknowledged him to have performed well across most of the curriculum, allotting him a top grade of 6 for history, physics, algebra, geometry, and descriptive geometry.[37] At seventeen, he enrolled in the four-year mathematics and physics teaching diploma program at the Federal polytechnic school. Marie Winteler, a year older than him, took up a teaching post in Olsberg, Switzerland.[35]

The five other polytechnic school freshmen following the same course as Einstein included just one woman, a twenty year old Serbian, Mileva Marić. Over the next few years, the pair spent many hours discussing their shared interests and learning about topics in physics that the polytechnic school's lectures did not cover. In his letters to Marić, Einstein confessed that exploring science with her by his side was much more enjoyable than reading a textbook in solitude. Eventually the two students became not only friends but also lovers.[38]

Historians of physics are divided on the question of the extent to which Marić contributed to the insights of Einstein's annus mirabilis publications. There is at least some evidence that he was influenced by her scientific ideas,[38][39][40] but there are scholars who doubt whether her impact on his thought was of any great significance at all.[41][42][43][44]

Marriages, relationships and children

Albert Einstein and Mileva Marić Einstein, 1912

Albert Einstein and Mileva Marić Einstein, 1912 Albert Einstein and Elsa Einstein, 1930

Albert Einstein and Elsa Einstein, 1930

Correspondence between Einstein and Marić, discovered and published in 1987, revealed that in early 1902, while Marić was visiting her parents in Novi Sad, she gave birth to a daughter, Lieserl. When Marić returned to Switzerland it was without the child, whose fate is uncertain. A letter of Einstein's that he wrote in September 1903 suggests that the girl was either given up for adoption or died of scarlet fever in infancy.[45][46]

Einstein and Marić married in January 1903. In May 1904, their son Hans Albert was born in Bern, Switzerland. Their son Eduard was born in Zürich in July 1910. In letters that Einstein wrote to Marie Winteler in the months before Eduard's arrival, he described his love for his wife as "misguided" and mourned the "missed life" that he imagined he would have enjoyed if he had married Winteler instead: "I think of you in heartfelt love every spare minute and am so unhappy as only a man can be."[47]

In 1912, Einstein entered into a relationship with Elsa Löwenthal, who was both his first cousin on his mother's side and his second cousin on his father's.[48][49][50] When Marić learned of his infidelity soon after moving to Berlin with him in April 1914, she returned to Zürich, taking Hans Albert and Eduard with her.[38] Einstein and Marić were granted a divorce on 14 February 1919 on the grounds of having lived apart for five years.[51][52] As part of the divorce settlement, Einstein agreed that if he were to win a Nobel Prize, he would give the money that he received to Marić; she had to wait only two years before her foresight in extracting this promise from him was rewarded.[53]

Einstein married Löwenthal in 1919.[54][55] In 1923, he began a relationship with a secretary named Betty Neumann, the niece of his close friend Hans Mühsam.[56][57][58][59] Löwenthal nevertheless remained loyal to him, accompanying him when he emigrated to the United States in 1933. In 1935, she was diagnosed with heart and kidney problems. She died in December 1936.[60]

A volume of Einstein's letters released by Hebrew University of Jerusalem in 2006[61] added further names to the catalog of women with whom he was romantically involved. They included Margarete Lebach (a blonde Austrian), Estella Katzenellenbogen (the rich owner of a florist business), Toni Mendel (a wealthy Jewish widow) and Ethel Michanowski (a Berlin socialite), with whom he spent time and from whom he accepted gifts while married to Löwenthal.[62][63] After being widowed, Einstein was briefly in a relationship with Margarita Konenkova, thought by some to be a Russian spy; her husband, the Russian sculptor Sergei Konenkov, created the bronze bust of Einstein at the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton.[64][65][failed verification]

Following an episode of acute mental illness at about the age of twenty, Einstein's son Eduard was diagnosed with schizophrenia.[66] He spent the remainder of his life either in the care of his mother or in temporary confinement in an asylum. After her death, he was committed permanently to Burghölzli, the Psychiatric University Hospital in Zürich.[67]

1902–1909: Assistant at the Swiss Patent Office

Einstein graduated from the Federal polytechnic school in 1900, duly certified as competent to teach mathematics and physics.[68] His successful acquisition of Swiss citizenship in February 1901[69] was not followed by the usual sequel of conscription; the Swiss authorities deemed him medically unfit for military service. He found that Swiss schools too appeared to have no use for him, failing to offer him a teaching position despite the almost two years that he spent applying for one. Eventually it was with the help of Marcel Grossmann's father that he secured a post in Bern at the Swiss Patent Office,[70][71] as an assistant examiner – level III.[72][73]

Patent applications that landed on Einstein's desk for his evaluation included ideas for a gravel sorter and an electric typewriter.[73] His employers were pleased enough with his work to make his position permanent in 1903, although they did not think that he should be promoted until he had "fully mastered machine technology".[74] It is conceivable that his labors at the patent office had a bearing on his development of his special theory of relativity. He arrived at his revolutionary ideas about space, time and light through thought experiments about the transmission of signals and the synchronization of clocks, matters which also figured in some of the inventions submitted to him for assessment.[15]

In 1902, Einstein and some friends whom he had met in Bern formed a group that held regular meetings to discuss science and philosophy. Their choice of a name for their club, the Olympia Academy, was an ironic comment upon its far from Olympian status. Sometimes they were joined by Marić, who limited her participation in their proceedings to careful listening.[75] The thinkers whose works they reflected upon included Henri Poincaré, Ernst Mach and David Hume, all of whom significantly influenced Einstein's own subsequent ideas and beliefs.[76]

1900–1905: First scientific papers

Einstein's 1905 dissertation, Eine neue Bestimmung der Moleküldimensione ("A new determination of molecular dimensions")

Einstein's 1905 dissertation, Eine neue Bestimmung der Moleküldimensione ("A new determination of molecular dimensions")

Einstein's first paper, "Folgerungen aus den Capillaritätserscheinungen" ("Conclusions drawn from the phenomena of capillarity"), in which he proposed a model of intermolecular attraction that he afterwards disavowed as worthless, was published in the journal Annalen der Physik in 1900.[77][78] His 24-page doctoral dissertation also addressed a topic in molecular physics. Titled "Eine neue Bestimmung der Moleküldimensionen" ("A New Determination of Molecular Dimensions") and dedicated to his friend Marcel Grossman, it was completed on 30 April 1905[79] and approved by Professor Alfred Kleiner of the University of Zurich three months later. (Einstein was formally awarded his PhD on 15 January 1906.)[79][80][81] Four other pieces of work that Einstein completed in 1905—his famous papers on the photoelectric effect, Brownian motion, his special theory of relativity and the equivalence of mass and energy—have led to the year's being celebrated as an annus mirabilis for physics almost as wonderful as 1666 (the year in which Isaac Newton experienced his greatest epiphanies). The publications deeply impressed Einstein's contemporaries.[82]

1908–1933: Early academic career

Einstein's sabbatical as a civil servant approached its end in 1908, when he secured a junior teaching position at the University of Bern. In 1909, a lecture on relativistic electrodynamics that he gave at the University of Zurich, much admired by Alfred Kleiner, led to Zürich's luring him away from Bern with a newly created associate professorship.[83] Promotion to a full professorship followed in April 1911, when he accepted a chair at the German Charles-Ferdinand University in Prague, a move which required him to become an Austrian citizen of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.[84][85] His time in Prague saw him producing eleven research papers.[86] Einstein in 1904, age 25

Einstein in 1904, age 25 Olympia Academy founders: Conrad Habicht, Maurice Solovine, and Einstein

Olympia Academy founders: Conrad Habicht, Maurice Solovine, and Einstein

In July 1912, he returned to his alma mater, the ETH Zurich, to take up a chair in theoretical physics. His teaching activities there centred on thermodynamics and analytical mechanics, and his research interests included the molecular theory of heat, continuum mechanics and the development of a relativistic theory of gravitation. In his work on the latter topic, he was assisted by his friend, Marcel Grossmann, whose knowledge of the kind of mathematics required was greater than his own.[87]

In the spring of 1913, two German visitors, Max Planck and Walther Nernst, called upon Einstein in Zürich in the hope of persuading him to relocate to Berlin.[88] They offered him membership of the Prussian Academy of Sciences, the directorship of the planned Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics and a chair at the Humboldt University of Berlin that would allow him to pursue his research supported by a professorial salary but with no teaching duties to burden him.[49] Their invitation was all the more appealing to him because Berlin happened to be the home of his latest girlfriend, Elsa Löwenthal.[88] He duly joined the Academy on 24 July 1913,[89] and moved into an apartment in the Berlin district of Dahlem on 1 April 1914.[49] He was installed in his Humboldt University position shortly thereafter.[89]

The outbreak of the First World War in July 1914 marked the beginning of Einstein's gradual estrangement from the nation of his birth. When the "Manifesto of the Ninety-Three" was published in October 1914—a document signed by a host of prominent German thinkers that justified Germany's belligerence—Einstein was one of the few German intellectuals to distance himself from it and sign the alternative, eirenic "Manifesto to the Europeans" instead.[90][91] But this expression of his doubts about German policy did not prevent him from being elected to a two-year term as president of the German Physical Society in 1916.[92] And when the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics opened its doors the following year—its foundation delayed because of the war—Einstein was appointed its first director, just as Planck and Nernst had promised.[93]

Einstein was elected a Foreign Member of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1920,[94] and a Foreign Member of the Royal Society in 1921. In 1922, he was awarded the 1921 Nobel Prize in Physics "for his services to Theoretical Physics, and especially for his discovery of the law of the photoelectric effect".[7] At this point some physicists still regarded the general theory of relativity sceptically, and the Nobel citation displayed a degree of doubt even about the work on photoelectricity that it acknowledged: it did not assent to Einstein's notion of the particulate nature of light, which only won over the entire scientific community when S. N. Bose derived the Planck spectrum in 1924. That same year, Einstein was elected an International Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.[95] Britain's closest equivalent of the Nobel award, the Royal Society's Copley Medal, was not hung around Einstein's neck until 1925.[1] He was elected an International Member of the American Philosophical Society in 1930.[96]

Einstein resigned from the Prussian Academy in March 1933. His accomplishments in Berlin had included the completion of the general theory of relativity, proving the Einstein–de Haas effect, contributing to the quantum theory of radiation, and the development of Bose–Einstein statistics.[49]

1919: Putting general relativity to the test

The New York Times reported confirmation of the bending of light by gravitation after observations (made in Príncipe and Sobral) of the 29 May 1919 eclipse were presented to a joint meeting in London of the Royal Society and the Royal Astronomical Society on 6 November 1919.[97]

The New York Times reported confirmation of the bending of light by gravitation after observations (made in Príncipe and Sobral) of the 29 May 1919 eclipse were presented to a joint meeting in London of the Royal Society and the Royal Astronomical Society on 6 November 1919.[97]

In 1907, Einstein reached a milestone on his long journey from his special theory of relativity to a new idea of gravitation with the formulation of his equivalence principle, which asserts that an observer in an infinitesimally small box falling freely in a gravitational field would be unable to find any evidence that the field exists. In 1911, he used the principle to estimate the amount by which a ray of light from a distant star would be bent by the gravitational pull of the Sun as it passed close to the Sun's photosphere (that is, the Sun's apparent surface). He reworked his calculation in 1913, having now found a way to model gravitation with the Riemann curvature tensor of a non-Euclidean four-dimensional spacetime. By the fall of 1915, his reimagining of the mathematics of gravitation in terms of Riemannian geometry was complete, and he applied his new theory not just to the behavior of the Sun as a gravitational lens but also to another astronomical phenomenon, the precession of the perihelion of Mercury (a slow drift in the point in Mercury's elliptical orbit at which it approaches the Sun most closely).[49][98] A total eclipse of the Sun that took place on 29 May 1919 provided an opportunity to put his theory of gravitational lensing to the test, and observations performed by Sir Arthur Eddington yielded results that were consistent with his calculations. Eddington's work was reported at length in newspapers around the world. On 7 November 1919, for example, the leading British newspaper, The Times, printed a banner headline that read: "Revolution in Science – New Theory of the Universe – Newtonian Ideas Overthrown".[99]

1921–1923: Coming to terms with fame

Einstein's official portrait after receiving the 1921 Nobel Prize for Physics

Einstein's official portrait after receiving the 1921 Nobel Prize for Physics

With Eddington's eclipse observations widely reported not just in academic journals but by the popular press as well, Einstein became "perhaps the world's first celebrity scientist", a genius who had shattered a paradigm that had been basic to physicists' understanding of the universe since the seventeenth century.[100]

Einstein began his new life as an intellectual icon in America, where he arrived on 2 April 1921. He was welcomed to New York City by Mayor John Francis Hylan, and then spent three weeks giving lectures and attending receptions.[101] He spoke several times at Columbia University and Princeton, and in Washington, he visited the White House with representatives of the National Academy of Sciences. He returned to Europe via London, where he was the guest of the philosopher and statesman Viscount Haldane. He used his time in the British capital to meet several people prominent in British scientific, political or intellectual life, and to deliver a lecture at King's College.[102][103] In July 1921, he published an essay, "My First Impression of the U.S.A.", in which he sought to sketch the American character, much as had Alexis de Tocqueville in Democracy in America (1835).[104] He wrote of his transatlantic hosts in highly approving terms: "What strikes a visitor is the joyous, positive attitude to life ... The American is friendly, self-confident, optimistic, and without envy."[105]

In 1922, Einstein's travels were to the old world rather than the new. He devoted six months to a tour of Asia that saw him speaking in Japan, Singapore and Sri Lanka (then known as Ceylon). After his first public lecture in Tokyo, he met Emperor Yoshihito and his wife at the Imperial Palace, with thousands of spectators thronging the streets in the hope of catching a glimpse of him. (In a letter to his sons, he wrote that Japanese people seemed to him to be generally modest, intelligent and considerate, and to have a true appreciation of art.[106] But his picture of them in his diary was less flattering: "[the] intellectual needs of this nation seem to be weaker than their artistic ones – natural disposition?" His journal also contains views of China and India which were uncomplimentary. Of Chinese people, he wrote that "even the children are spiritless and look obtuse... It would be a pity if these Chinese supplant all other races. For the likes of us the mere thought is unspeakably dreary".[107][108]) He was greeted with even greater enthusiasm on the last leg of his tour, in which he spent twelve days in Mandatory Palestine, newly entrusted to British rule by the League of Nations in the aftermath of the First World War. Sir Herbert Samuel, the British High Commissioner, welcomed him with a degree of ceremony normally only accorded to a visiting head of state, including a cannon salute. One reception held in his honor was stormed by people determined to hear him speak: he told them that he was happy that Jews were beginning to be recognized as a force in the world.[109]

Einstein's decision to tour the eastern hemisphere in 1922 meant that he was unable to go to Stockholm in the December of that year to participate in the Nobel prize ceremony. His place at the traditional Nobel banquet was taken by a German diplomat, who gave a speech praising him not only as a physicist but also as a campaigner for peace.[110] A two week visit to Spain that he undertook in 1923 saw him collecting another award, a membership of the Spanish Academy of Sciences signified by a diploma handed to him by King Alfonso XIII. (His Spanish trip also gave him a chance to meet a fellow Nobel laureate, the neuroanatomist Santiago Ramón y Cajal.)[111]