Why the British Columbia Conservation Officer Service should be designated as a provincial police se

British Columbia’s proposed new police law, Bill 17, has excluded provincial armed environmental law enforcement from its legal definition of “police.” Why does this matter?

At the heart of this issue lies a fundamental legal question. Should environmental police services be treated in the law as regular police and, crucially, subject to the same regulatory oversight?

For many officers, academics and members of the general public alike, the answer is a resounding yes. Especially as a means to curtail the unnecessary use of lethal force on wildlife, the para-militarization of environmental police services and a history of questionable arrests. This is in addition to media scrutiny of investigative practices involving both human deaths and the death of domestic animals.

However, in Bill 17 the B.C. government has so far resisted calls for change.

If armed provincial officers are going to dress like police, carry police weapons and related equipment, drive police-like vehicles and be appointed like police then they should have the same independent oversight as the police. Modern accountability and transparency mechanisms provide a model and structure for individual officer restraint and broader agency accountability for the public.

More transparency and accountability for policing actions and officer conduct could lead to less lethal force on wildlife and a reduction in negative public interactions.

British Columbia Conservation Officer Service

The B.C. Conservation Officer Service (BCCOS) is the province’s formal, and fully armed, frontline environmental police service which specializes in “public safety as it relates to human/wildlife conflict” — with an additional mandate to manage “complex commercial environmental and industrial investigations and compliance and enforcement services”.

Individual officers of the BCCOS are designated as special provincial constables under section 9 of the current Police Act. However, the BCCOS as an agency is not designated as a police service in current law.

This creates a legal conflict between officers acting like police in the public sphere but not held as accountable as other police services because they work for a non-policing agency. I experienced this conflict first-hand during my time as an officer with the BCCOS.

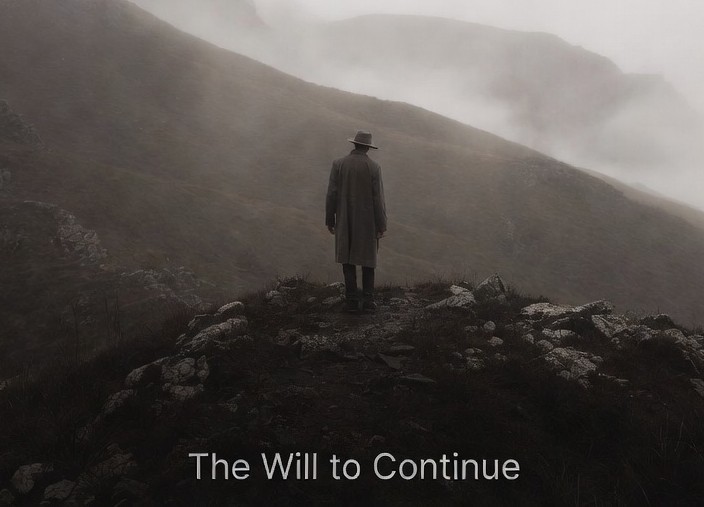

Two men stand by a car.

Surrey police officers are seen in Surrey, B.C., in July 2023. The BCCOS operates as a fully armed police-like service without the same degree of oversight as other police services across the province. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Darryl Dyck

The BCCOS was formerly a part of the B.C. Provincial Police Force and provided an armed environmental police service since 1871.

Since 2003, however, the BCCOS has been structured under Section 106 of the Environmental Management Act. This legislation was written primarily for pollution control and waste management and was never intended to take the place of the Police Act or allow a police-like service to operate in the province.

This cumbersome legal arrangement — where a police-like force is controlled by a piece of legislation not intended for policing — has directly inhibited attempts at greater independent oversight, accountability, and review of police actions.

Bill 17 had an opportunity to correct this by properly designating the BCCOS as a provincial police British Columbia’s proposed new police law, Bill 17, has excluded provincial armed environmental law enforcement from its legal definition of “police.” Why does this matter?

At the heart of this issue lies a fundamental legal question. Should environmental police services be treated in the law as regular police and, crucially, subject to the same regulatory oversight?

For many officers, academics and members of the general public alike, the answer is a resounding yes. Especially as a means to curtail the unnecessary use of lethal force on wildlife, the para-militarization of environmental police services and a history of questionable arrests. This is in addition to media scrutiny of investigative practices involving both human deaths and the death of domestic animals.

However, in Bill 17 the B.C. government has so far resisted calls for change.

If armed provincial officers are going to dress like police, carry police weapons and related equipment, drive police-like vehicles and be appointed like police then they should have the same independent oversight as the police. Modern accountability and transparency mechanisms provide a model and structure for individual officer restraint and broader agency accountability for the public.

More transparency and accountability for policing actions and officer conduct could lead to less lethal force on wildlife and a reduction in negative public interactions.

British Columbia Conservation Officer Service

The B.C. Conservation Officer Service (BCCOS) is the province’s formal, and fully armed, frontline environmental police service which specializes in “public safety as it relates to human/wildlife conflict” — with an additional mandate to manage “complex commercial environmental and industrial investigations and compliance and enforcement services”.

Individual officers of the BCCOS are designated as special provincial constables under section 9 of the current Police Act. However, the BCCOS as an agency is not designated as a police service in current law.

This creates a legal conflict between officers acting like police in the public sphere but not held as accountable as other police services because they work for a non-policing agency. I experienced this conflict first-hand during my time as an officer with the BCCOS.

Two men stand by a car.

Surrey police officers are seen in Surrey, B.C., in July 2023. The BCCOS operates as a fully armed police-like service without the same degree of oversight as other police services across the province. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Darryl Dyck

The BCCOS was formerly a part of the B.C. Provincial Police Force and provided an armed environmental police service since 1871.

Since 2003, however, the BCCOS has been structured under Section 106 of the Environmental Management Act. This legislation was written primarily for pollution control and waste management and was never intended to take the place of the Police Act or allow a police-like service to operate in the province.

This cumbersome legal arrangement — where a police-like force is controlled by a piece of legislation not intended for policing — has directly inhibited attempts at greater independent oversight, accountability, and review of police actions.

Bill 17 had an opportunity to correct this by properly designating the BCBritish Columbia’s proposed new police law, Bill 17, has excluded provincial armed environmental law enforcement from its legal definition of “police.” Why does this matter?

At the heart of this issue lies a fundamental legal question. Should environmental police services be treated in the law as regular police and, crucially, subject to the same regulatory oversight?

For many officers, academics and members of the general public alike, the answer is a resounding yes. Especially as a means to curtail the unnecessary use of lethal force on wildlife, the para-militarization of environmental police services and a history of questionable arrests. This is in addition to media scrutiny of investigative practices involving both human deaths and the death of domestic animals.

However, in Bill 17 the B.C. government has so far resisted calls for change.

If armed provincial officers are going to dress like police, carry police weapons and related equipment, drive police-like vehicles and be appointed like police then they should have the same independent oversight as the police. Modern accountability and transparency mechanisms provide a model and structure for individual officer restraint and broader agency accountability for the public.

More transparency and accountability for policing actions and officer conduct could lead to less lethal force on wildlife and a reduction in negative public interactions.

British Columbia Conservation Officer Service

The B.C. Conservation Officer Service (BCCOS) is the province’s formal, and fully armed, frontline environmental police service which specializes in “public safety as it relates to human/wildlife conflict” — with an additional mandate to manage “complex commercial environmental and industrial investigations and compliance and enforcement services”.

Individual officers of the BCCOS are designated as special provincial constables under section 9 of the current Police Act. However, the BCCOS as an agency is not designated as a police service in current law.

This creates a legal conflict between officers acting like police in the public sphere but not held as accountable as other police services because they work for a non-policing agency. I experienced this conflict first-hand during my time as an officer with the BCCOS.

Two men stand by a car.

Surrey police officers are seen in Surrey, B.C., in July 2023. The BCCOS operates as a fully armed police-like service without the same degree of oversight as other police services across the province. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Darryl Dyck

The BCCOS was formerly a part of the B.C. Provincial Police Force and provided an armed environmental police service since 1871.

Since 2003, however, the BCCOS has been structured under Section 106 of the Environmental Management Act. This legislation was written primarily for pollution control and waste management and was never intended to take the place of the Police Act or allow a police-like service to operate in the province.

This cumbersome legal arrangement — where a police-like force is controlled by a piece of legislation not intended for policing — has directly inhibited attempts at greater independent oversight, accountability, and review of police actions.

Bill 17 had an opportunity to correct this by properly designating the BCBritish Columbia’s proposed new police law, Bill 17, has excluded provincial armed environmental law enforcement from its legal definition of “police.” Why does this matter?

At the heart of this issue lies a fundamental legal question. Should environmental police services be treated in the law as regular police and, crucially, subject to the same regulatory oversight?

For many officers, academics and members of the general public alike, the answer is a resounding yes. Especially as a means to curtail the unnecessary use of lethal force on wildlife, the para-militarization of environmental police services and a history of questionable arrests. This is in addition to media scrutiny of investigative practices involving both human deaths and the death of domestic animals.

However, in Bill 17 the B.C. government has so far resisted calls for change.

If armed provincial officers are going to dress like police, carry police weapons and related equipment, drive police-like vehicles and be appointed like police then they should have the same independent oversight as the police. Modern accountability and transparency mechanisms provide a model and structure for individual officer restraint and broader agency accountability for the public.

More transparency and accountability for policing actions and officer conduct could lead to less lethal force on wildlife and a reduction in negative public interactions.

British Columbia Conservation Officer Service

The B.C. Conservation Officer Service (BCCOS) is the province’s formal, and fully armed, frontline environmental police service which specializes in “public safety as it relates to human/wildlife conflict” — with an additional mandate to manage “complex commercial environmental and industrial investigations and compliance and enforcement services”.

Individual officers of the BCCOS are designated as special provincial constables under section 9 of the current Police Act. However, the BCCOS as an agency is not designated as a police service in current law.

This creates a legal conflict between officers acting like police in the public sphere but not held as accountable as other police services because they work for a non-policing agency. I experienced this conflict first-hand during my time as an officer with the BCCOS.

Two men stand by a car.

Surrey police officers are seen in Surrey, B.C., in July 2023. The BCCOS operates as a fully armed police-like service without the same degree of oversight as other police services across the province. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Darryl Dyck

The BCCOS was formerly a part of the B.C. Provincial Police Force and provided an armed environmental police service since 1871.

Since 2003, however, the BCCOS has been structured under Section 106 of the Environmental Management Act. This legislation was written primarily for pollution control and waste management and was never intended to take the place of the Police Act or allow a police-like service to operate in the province.

This cumbersome legal arrangement — where a police-like force is controlled by a piece of legislation not intended for policing — has directly inhibited attempts at greater independent oversight, accountability, and review of police actions.

Bill 17 had an opportunity to correct this by properly designating the BCBritish Columbia’s proposed new police law, Bill 17, has excluded provincial armed environmental law enforcement from its legal definition of “police.” Why does this matter?

At the heart of this issue lies a fundamental legal question. Should environmental police services be treated in the law as regular police and, crucially, subject to the same regulatory oversight?

For many officers, academics and members of the general public alike, the answer is a resounding yes. Especially as a means to curtail the unnecessary use of lethal force on wildlife, the para-militarization of environmental police services and a history of questionable arrests. This is in addition to media scrutiny of investigative practices involving both human deaths and the death of domestic animals.

However, in Bill 17 the B.C. government has so far resisted calls for change.

If armed provincial officers are going to dress like police, carry police weapons and related equipment, drive police-like vehicles and be appointed like police then they should have the same independent oversight as the police. Modern accountability and transparency mechanisms provide a model and structure for individual officer restraint and broader agency accountability for the public.

More transparency and accountability for policing actions and officer conduct could lead to less lethal force on wildlife and a reduction in negative public interactions.

British Columbia Conservation Officer Service

The B.C. Conservation Officer Service (BCCOS) is the province’s formal, and fully armed, frontline environmental police service which specializes in “public safety as it relates to human/wildlife conflict” — with an additional mandate to manage “complex commercial environmental and industrial investigations and compliance and enforcement services”.

Individual officers of the BCCOS are designated as special provincial constables under section 9 of the current Police Act. However, the BCCOS as an agency is not designated as a police service in current law.

This creates a legal conflict between officers acting like police in the public sphere but not held as accountable as other police services because they work for a non-policing agency. I experienced this conflict first-hand during my time as an officer with the BCCOS.

Two men stand by a car.

Surrey police officers are seen in Surrey, B.C., in July 2023. The BCCOS operates as a fully armed police-like service without the same degree of oversight as other police services across the province. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Darryl Dyck

The BCCOS was formerly a part of the B.C. Provincial Police Force and provided an armed environmental police service since 1871.

Since 2003, however, the BCCOS has been structured under Section 106 of the Environmental Management Act. This legislation was written primarily for pollution control and waste management and was never intended to take the place of the Police Act or allow a police-like service to operate in the province.

This cumbersome legal arrangement — where a police-like force is controlled by a piece of legislation not intended for policing — has directly inhibited attempts at greater independent oversight, accountability, and review of police actions.

Bill 17 had an opportunity to correct this by properly designating the BCBritish Columbia’s proposed new police law, Bill 17, has excluded provincial armed environmental law enforcement from its legal definition of “police.” Why does this matter?

At the heart of this issue lies a fundamental legal question. Should environmental police services be treated in the law as regular police and, crucially, subject to the same regulatory oversight?

For many officers, academics and members of the general public alike, the answer is a resounding yes. Especially as a means to curtail the unnecessary use of lethal force on wildlife, the para-militarization of environmental police services and a history of questionable arrests. This is in addition to media scrutiny of investigative practices involving both human deaths and the death of domestic animals.

However, in Bill 17 the B.C. government has so far resisted calls for change.

If armed provincial officers are going to dress like police, carry police weapons and related equipment, drive police-like vehicles and be appointed like police then they should have the same independent oversight as the police. Modern accountability and transparency mechanisms provide a model and structure for individual officer restraint and broader agency accountability for the public.

More transparency and accountability for policing actions and officer conduct could lead to less lethal force on wildlife and a reduction in negative public interactions.

British Columbia Conservation Officer Service

The B.C. Conservation Officer Service (BCCOS) is the province’s formal, and fully armed, frontline environmental police service which specializes in “public safety as it relates to human/wildlife conflict” — with an additional mandate to manage “complex commercial environmental and industrial investigations and compliance and enforcement services”.

Individual officers of the BCCOS are designated as special provincial constables under section 9 of the current Police Act. However, the BCCOS as an agency is not designated as a police service in current law.

This creates a legal conflict between officers acting like police in the public sphere but not held as accountable as other police services because they work for a non-policing agency. I experienced this conflict first-hand during my time as an officer with the BCCOS.

Two men stand by a car.

Surrey police officers are seen in Surrey, B.C., in July 2023. The BCCOS operates as a fully armed police-like service without the same degree of oversight as other police services across the province. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Darryl Dyck

The BCCOS was formerly a part of the B.C. Provincial Police Force and provided an armed environmental police service since 1871.

Since 2003, however, the BCCOS has been structured under Section 106 of the Environmental Management Act. This legislation was written primarily for pollution control and waste management and was never intended to take the place of the Police Act or allow a police-like service to operate in the province.

This cumbersome legal arrangement — where a police-like force is controlled by a piece of legislation not intended for policing — has directly inhibited attempts at greater independent oversight, accountability, and review of police actions.

Bill 17 had an opportunity to correct this by properly designating the BCBritish Columbia’s proposed new police law, Bill 17, has excluded provincial armed environmental law enforcement from its legal definition of “police.” Why does this matter?

At the heart of this issue lies a fundamental legal question. Should environmental police services be treated in the law as regular police and, crucially, subject to the same regulatory oversight?

For many officers, academics and members of the general public alike, the answer is a resounding yes. Especially as a means to curtail the unnecessary use of lethal force on wildlife, the para-militarization of environmental police services and a history of questionable arrests. This is in addition to media scrutiny of investigative practices involving both human deaths and the death of domestic animals.

However, in Bill 17 the B.C. government has so far resisted calls for change.

If armed provincial officers are going to dress like police, carry police weapons and related equipment, drive police-like vehicles and be appointed like police then they should have the same independent oversight as the police. Modern accountability and transparency mechanisms provide a model and structure for individual officer restraint and broader agency accountability for the public.

More transparency and accountability for policing actions and officer conduct could lead to less lethal force on wildlife and a reduction in negative public interactions.

British Columbia Conservation Officer Service

The B.C. Conservation Officer Service (BCCOS) is the province’s formal, and fully armed, frontline environmental police service which specializes in “public safety as it relates to human/wildlife conflict” — with an additional mandate to manage “complex commercial environmental and industrial investigations and compliance and enforcement services”.

Individual officers of the BCCOS are designated as special provincial constables under section 9 of the current Police Act. However, the BCCOS as an agency is not designated as a police service in current law.

This creates a legal conflict between officers acting like police in the public sphere but not held as accountable as other police services because they work for a non-policing agency. I experienced this conflict first-hand during my time as an officer with the BCCOS.

Two men stand by a car.

Surrey police officers are seen in Surrey, B.C., in July 2023. The BCCOS operates as a fully armed police-like service without the same degree of oversight as other police services across the province. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Darryl Dyck

The BCCOS was formerly a part of the B.C. Provincial Police Force and provided an armed environmental police service since 1871.

Since 2003, however, the BCCOS has been structured under Section 106 of the Environmental Management Act. This legislation was written primarily for pollution control and waste management and was never intended to take the place of the Police Act or allow a police-like service to operate in the province.

This cumbersome legal arrangement — where a police-like force is controlled by a piece of legislation not intended for policing — has directly inhibited attempts at greater independent oversight, accountability, and review of police actions.

Bill 17 had an opportunity to correct this by properly designating the BCBritish Columbia’s proposed new police law, Bill 17, has excluded provincial armed environmental law enforcement from its legal definition of “police.” Why does this matter?

At the heart of this issue lies a fundamental legal question. Should environmental police services be treated in the law as regular police and, crucially, subject to the same regulatory oversight?

For many officers, academics and members of the general public alike, the answer is a resounding yes. Especially as a means to curtail the unnecessary use of lethal force on wildlife, the para-militarization of environmental police services and a history of questionable arrests. This is in addition to media scrutiny of investigative practices involving both human deaths and the death of domestic animals.

However, in Bill 17 the B.C. government has so far resisted calls for change.

If armed provincial officers are going to dress like police, carry police weapons and related equipment, drive police-like vehicles and be appointed like police then they should have the same independent oversight as the police. Modern accountability and transparency mechanisms provide a model and structure for individual officer restraint and broader agency accountability for the public.

More transparency and accountability for policing actions and officer conduct could lead to less lethal force on wildlife and a reduction in negative public interactions.

British Columbia Conservation Officer Service

The B.C. Conservation Officer Service (BCCOS) is the province’s formal, and fully armed, frontline environmental police service which specializes in “public safety as it relates to human/wildlife conflict” — with an additional mandate to manage “complex commercial environmental and industrial investigations and compliance and enforcement services”.

Individual officers of the BCCOS are designated as special provincial constables under section 9 of the current Police Act. However, the BCCOS as an agency is not designated as a police service in current law.

This creates a legal conflict between officers acting like police in the public sphere but not held as accountable as other police services because they work for a non-policing agency. I experienced this conflict first-hand during my time as an officer with the BCCOS.

Two men stand by a car.

Surrey police officers are seen in Surrey, B.C., in July 2023. The BCCOS operates as a fully armed police-like service without the same degree of oversight as other police services across the province. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Darryl Dyck

The BCCOS was formerly a part of the B.C. Provincial Police Force and provided an armed environmental police service since 1871.

Since 2003, however, the BCCOS has been structured under Section 106 of the Environmental Management Act. This legislation was written primarily for pollution control and waste management and was never intended to take the place of the Police Act or allow a police-like service to operate in the province.

This cumbersome legal arrangement — where a police-like force is controlled by a piece of legislation not intended for policing — has directly inhibited attempts at greater independent oversight, accountability, and review of police actions.

Bill 17 had an opportunity to correct this by properly designating the BCCOS as a provincial police COS as a provincial police COS as a provincial police COS as a provincial police COS as a provincial police COS as a provincial police COS as a provincial police