cat

Cat

Temporal range: 9,500 years ago – present

Various types of cats

Domesticated

Scientific classification![]() Domain:EukaryotaKingdom:AnimaliaPhylum:ChordataClass:MammaliaOrder:CarnivoraSuborder:FeliformiaFamily:FelidaeSubfamily:FelinaeGenus:FelisSpecies:F. catus[1]Binomial nameFelis catus[1]

Domain:EukaryotaKingdom:AnimaliaPhylum:ChordataClass:MammaliaOrder:CarnivoraSuborder:FeliformiaFamily:FelidaeSubfamily:FelinaeGenus:FelisSpecies:F. catus[1]Binomial nameFelis catus[1]

Linnaeus, 1758[2]

The cat (Felis catus), commonly referred to as the domestic cat or house cat, is the only domesticated species in the family Felidae. Recent advances in archaeology and genetics have shown that the domestication of the cat occurred in the Near East around 7500 BC. It is commonly kept as a house pet and farm cat, but also ranges freely as a feral cat avoiding human contact. It is valued by humans for companionship and its ability to kill vermin. Its retractable claws are adapted to killing small prey like mice and rats. It has a strong, flexible body, quick reflexes, sharp teeth, and its night vision and sense of smell are well developed. It is a social species, but a solitary hunter and a crepuscular predator. Cat communication includes vocalizations like meowing, purring, trilling, hissing, growling, and grunting as well as cat body language. It can hear sounds too faint or too high in frequency for human ears, such as those made by small mammals. It also secretes and perceives pheromones.

Female domestic cats can have kittens from spring to late autumn in temperate zones and throughout the year in equatorial regions, with litter sizes often ranging from two to five kittens. Domestic cats are bred and shown at events as registered pedigreed cats, a hobby known as cat fancy. Animal population control of cats may be achieved by spaying and neutering, but their proliferation and the abandonment of pets has resulted in large numbers of feral cats worldwide, contributing to the extinction of bird, mammal and reptile species.

As of 2017, the domestic cat was the second most popular pet in the United States, with 95.6 million cats owned and around 42 million households owning at least one cat. In the United Kingdom, 26% of adults have a cat, with an estimated population of 10.9 million pet cats as of 2020. As of 2021, there were an estimated 220 million owned and 480 million stray cats in the world.

Etymology and naming

The origin of the English word cat, Old English catt, is thought to be the Late Latin word cattus, which was first used at the beginning of the 6th century.[4] The Late Latin word may be derived from an unidentified African language.[5] The Nubian word kaddîska 'wildcat' and Nobiin kadīs are possible sources or cognates.[6] The Nubian word may be a loan from Arabic قَطّ qaṭṭ ~ قِطّ qiṭṭ.[citation needed]

The forms might also have derived from an ancient Germanic word that was imported into Latin and then into Greek, Syriac, and Arabic.[7] The word may be derived from Germanic and Northern European languages, and ultimately be borrowed from Uralic, cf. Northern Sámi gáđfi, 'female stoat', and Hungarian hölgy, 'lady, female stoat'; from Proto-Uralic *käďwä, 'female (of a furred animal)'.[8]

The English puss, extended as pussy and pussycat, is attested from the 16th century and may have been introduced from Dutch poes or from Low German puuskatte, related to Swedish kattepus, or Norwegian pus, pusekatt. Similar forms exist in Lithuanian puižė and Irish puisín or puiscín. The etymology of this word is unknown, but it may have arisen from a sound used to attract a cat.[9][10]

A male cat is called a tom or tomcat[11] (or a gib,[12] if neutered). A female is called a queen[13] or a molly,[14][user-generated source?] if spayed, especially in a cat-breeding context. A juvenile cat is referred to as a kitten. In Early Modern English, the word kitten was interchangeable with the now-obsolete word catling.[15]

A group of cats can be referred to as a clowder or a glaring.[16]

Taxonomy

The scientific name Felis catus was proposed by Carl Linnaeus in 1758 for a domestic cat.[1][2] Felis catus domesticus was proposed by Johann Christian Polycarp Erxleben in 1777.[3] Felis daemon proposed by Konstantin Satunin in 1904 was a black cat from the Transcaucasus, later identified as a domestic cat.[17][18]

In 2003, the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature ruled that the domestic cat is a distinct species, namely Felis catus.[19][20] In 2007, the modern domesticated subspecies F. silvestris catus sampled worldwide was considered to have likely descended from the Near Eastern wildcat (F. lybica) following results of phylogenetic research.[21][22][a] In 2017, the IUCN Cat Classification Taskforce followed the recommendation of the ICZN in regarding the domestic cat as a distinct species, Felis catus.[23]

Evolution

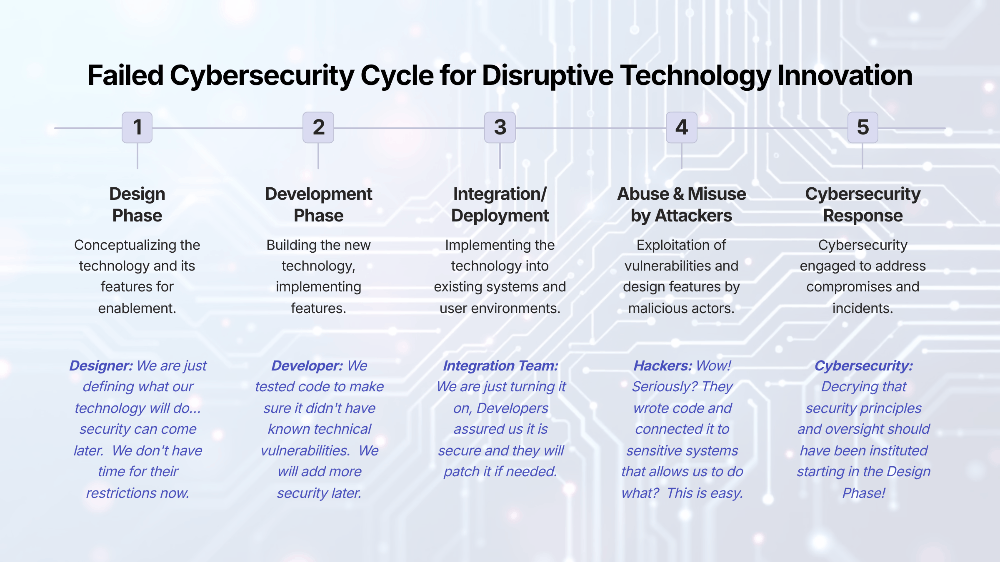

Main article: Cat evolution Skulls of a wildcat (top left), a housecat (top right), and a hybrid between the two. (bottom center)

Skulls of a wildcat (top left), a housecat (top right), and a hybrid between the two. (bottom center)

The domestic cat is a member of the Felidae, a family that had a common ancestor about 10 to 15 million years ago.[24] The evolutionary radiation of the Felidae began in Asia during the Miocene around 8.38 to 14.45 million years ago.[25] Analysis of mitochondrial DNA of all Felidae species indicates a radiation at 6.46 to 16.76 million years ago.[26] The genus Felis genetically diverged from other Felidae around 6 to 7 million years ago.[25] Results of phylogenetic research shows that the wild members of this genus evolved through sympatric or parapatric speciation, whereas the domestic cat evolved through artificial selection.[27] The domestic cat and its closest wild ancestor are diploid and both possess 38 chromosomes[28] and roughly 20,000 genes.[29]

Phylogenetic relationships of the domestic cat as derived through analysis of

nuclear DNA:[25][26] Felidae Pantherinae

Felinae other Felinae lineages

Felis Jungle cat (F. chaus) ![]() Black-footed cat (F. nigripes)

Black-footed cat (F. nigripes)

Sand cat (F. margarita)

Chinese mountain cat (F. bieti)

African wildcat (F. lybica)

European wildcat (F. silvestris)  Domestic cat

Domestic cat  mitochondrial DNA:[30] Felis Sand cat (F. margarita)

mitochondrial DNA:[30] Felis Sand cat (F. margarita)

Chinese mountain cat (F. bieti)

European wildcat (F. silvestris)  African wildcat Southern African wildcat (F. l. cafra)

African wildcat Southern African wildcat (F. l. cafra)

Asiatic wildcat (F. l. ornata)

Near Eastern wildcat

Domestic cat

Domestication

See also: Domestication of the cat and Cats in ancient Egypt A cat eating a fish under a chair, a mural in an Egyptian tomb dating to the 15th century BC

A cat eating a fish under a chair, a mural in an Egyptian tomb dating to the 15th century BC

It was long thought that the domestication of the cat began in ancient Egypt, where cats were venerated from around 3100 BC,[31][32] However, the earliest known indication for the taming of an African wildcat was excavated close by a human Neolithic grave in Shillourokambos, southern Cyprus, dating to about 7500–7200 BC. Since there is no evidence of native mammalian fauna on Cyprus, the inhabitants of this Neolithic village most likely brought the cat and other wild mammals to the island from the Middle Eastern mainland.[33] Scientists therefore assume that African wildcats were attracted to early human settlements in the Fertile Crescent by rodents, in particular the house mouse (Mus musculus), and were tamed by Neolithic farmers. This mutual relationship between early farmers and tamed cats lasted thousands of years. As agricultural practices spread, so did tame and domesticated cats.[30][34] Wildcats of Egypt contributed to the maternal gene pool of the domestic cat at a later time.[35]

The earliest known evidence for the occurrence of the domestic cat in Greece dates to around 1200 BC. Greek, Phoenician, Carthaginian and Etruscan traders introduced domestic cats to southern Europe.[36] During the Roman Empire they were introduced to Corsica and Sardinia before the beginning of the 1st millennium.[37] By the 5th century BC, they were familiar animals around settlements in Magna Graecia and Etruria.[38] By the end of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century, the Egyptian domestic cat lineage had arrived in a Baltic Sea port in northern Germany.[35]

The leopard cat (Prionailurus bengalensis) was tamed independently in China around 5500 BC. This line of partially domesticated cats leaves no trace in the domestic cat populations of today.[39]

During domestication, cats have undergone only minor changes in anatomy and behavior, and they are still capable of surviving in the wild. Several natural behaviors and characteristics of wildcats may have pre-adapted them for domestication as pets. These traits include their small size, social nature, obvious body language, love of play, and high intelligence. Since they practice rigorous grooming habits and have an instinctual drive to bury and hide their urine and feces, they are generally much less messy than other domesticated animals. Captive Leopardus cats may also display affectionate behavior toward humans but were not domesticated.[40] House cats often mate with feral cats.[41] Hybridisation between domestic and other Felinae species is also possible, producing hybrids such as the Kellas cat in Scotland.[42][43]

Development of cat breeds started in the mid 19th century.[44] An analysis of the domestic cat genome revealed that the ancestral wildcat genome was significantly altered in the process of domestication, as specific mutations were selected to develop cat breeds.[45] Most breeds are founded on random-bred domestic cats. Genetic diversity of these breeds varies between regions, and is lowest in purebred populations, which show more than 20 deleterious genetic disorders.[46]

Characteristics

Main article: Cat anatomy

Size

Diagram of the general anatomy of a male domestic cat

Diagram of the general anatomy of a male domestic cat

The domestic cat has a smaller skull and shorter bones than the European wildcat.[47] It averages about 46 cm (18 in) in head-to-body length and 23–25 cm (9.1–9.8 in) in height, with about 30 cm (12 in) long tails. Males are larger than females.[48] Adult domestic cats typically weigh 4–5 kg (8.8–11.0 lb).[27]

Skeleton

Cats have seven cervical vertebrae (as do most mammals); 13 thoracic vertebrae (humans have 12); seven lumbar vertebrae (humans have five); three sacral vertebrae (as do most mammals, but humans have five); and a variable number of caudal vertebrae in the tail (humans have only three to five vestigial caudal vertebrae, fused into an internal coccyx).[49]: 11 The extra lumbar and thoracic vertebrae account for the cat's spinal mobility and flexibility. Attached to the spine are 13 ribs, the shoulder, and the pelvis.[49]: 16 Unlike human arms, cat forelimbs are attached to the shoulder by free-floating clavicle bones which allow them to pass their body through any space into which they can fit their head.[50]

Skull

Cat skull

Cat skull A cat with exposed teeth and claws

A cat with exposed teeth and claws

The cat skull is unusual among mammals in having very large eye sockets and a powerful specialized jaw.[51]: 35 Within the jaw, cats have teeth adapted for killing prey and tearing meat. When it overpowers its prey, a cat delivers a lethal neck bite with its two long canine teeth, inserting them between two of the prey's vertebrae and severing its spinal cord, causing irreversible paralysis and death.[52] Compared to other felines, domestic cats have narrowly spaced canine teeth relative to the size of their jaw, which is an adaptation to their preferred prey of small rodents, which have small vertebrae.[52]

The premolar and first molar together compose the carnassial pair on each side of the mouth, which efficiently shears meat into small pieces, like a pair of scissors. These are vital in feeding, since cats' small molars cannot chew food effectively, and cats are largely incapable of mastication.[51]: 37 Cats tend to have better teeth than most humans, with decay generally less likely because of a thicker protective layer of enamel, a less damaging saliva, less retention of food particles between teeth, and a diet mostly devoid of sugar. Nonetheless, they are subject to occasional tooth loss and infection.[53]

Claws

Shed claw sheaths

Shed claw sheaths

Cats have protractible and retractable claws.[54] In their normal, relaxed position, the claws are sheathed with the skin and fur around the paw's toe pads. This keeps the claws sharp by preventing wear from contact with the ground and allows for the silent stalking of prey. The claws on the forefeet are typically sharper than those on the hindfeet.[55] Cats can voluntarily extend their claws on one or more paws. They may extend their claws in hunting or self-defense, climbing, kneading, or for extra traction on soft surfaces. Cats shed the outside layer of their claw sheaths when scratching rough surfaces.[56]

Most cats have five claws on their front paws and four on their rear paws. The dewclaw is proximal to the other claws. More proximally is a protrusion which appears to be a sixth "finger". This special feature of the front paws on the inside of the wrists has no function in normal walking but is thought to be an antiskidding device used while jumping. Some cat breeds are prone to having extra digits ("polydactyly").[57] Polydactylous cats occur along North America's northeast coast and in Great Britain.[58]

Ambulation

The cat is digitigrade. It walks on the toes, with the bones of the feet making up the lower part of the visible leg.[59] Unlike most mammals, it uses a "pacing" gait and moves both legs on one side of the body before the legs on the other side. It registers directly by placing each hind paw close to the track of the corresponding fore paw, minimizing noise and visible tracks. This also provides sure footing for hind paws when navigating rough terrain. As it speeds up from walking to trotting, its gait changes to a "diagonal" gait: The diagonally opposite hind and fore legs move simultaneously.[60]

Balance

Duration: 13 minutes and 37 seconds.

13:37

Comparison of cat righting reflexes in gravity and zero gravity

Cats are generally fond of sitting in high places or perching. A higher place may serve as a concealed site from which to hunt; domestic cats strike prey by pouncing from a perch such as a tree branch. Another possible explanation is that height gives the cat a better observation point, allowing it to survey its territory. A cat falling from heights of up to 3 m (9.8 ft) can right itself and land on its paws.[61]

During a fall from a high place, a cat reflexively twists its body and rights itself to land on its feet using its acute sense of balance and flexibility. This reflex is known as the cat righting reflex.[62] A cat always rights itself in the same way during a fall, if it has enough time to do so, which is the case in falls of 90 cm (3.0 ft) or more.[63] How cats are able to right themselves when falling has been investigated as the "falling cat problem".[64]

Coats

Main article: Cat coat genetics

The cat family (Felidae) can pass down many colors and patterns to their offspring. The domestic cat genes MC1R and ASIP allow for the variety of colors in coats. The feline ASIP gene consists of three coding exons.[65] Three novel microsatellite markers linked to ASIP were isolated from a domestic cat BAC clone containing this gene to perform linkage analysis in 89 domestic cats segregated for melanism. The domestic cat family demonstrated a cosegregation between the ASIP allele and coat black coloration.